By Megan Lutes

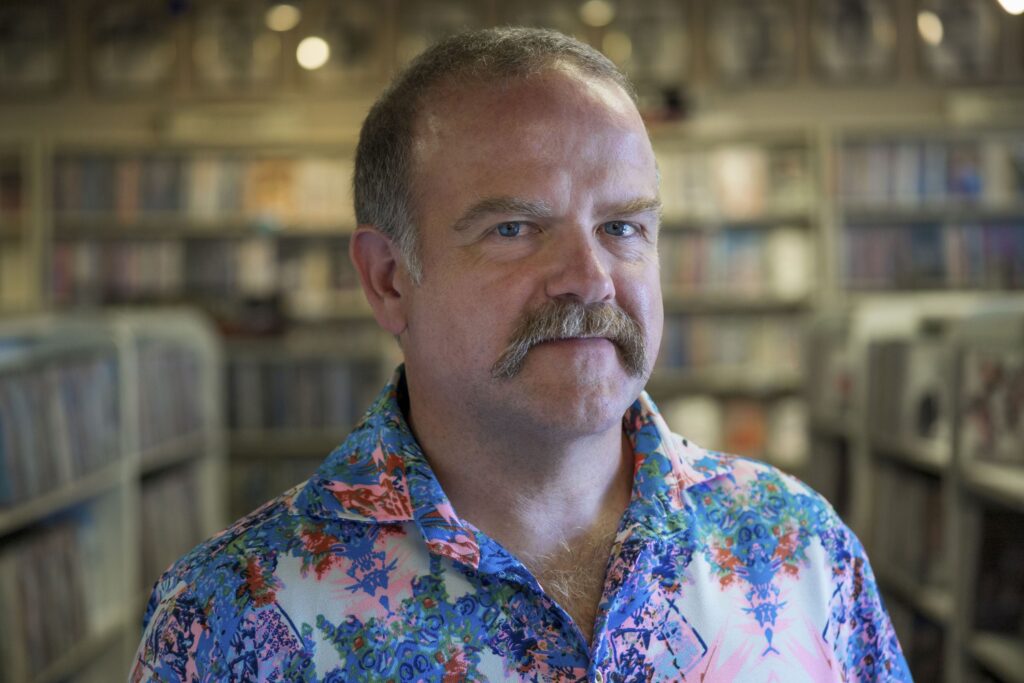

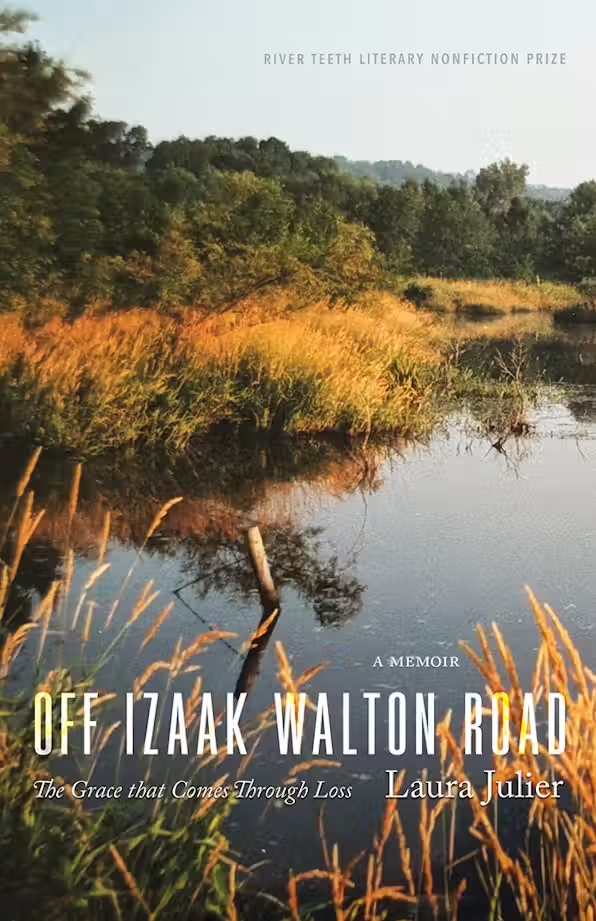

Laura Julier, former editor of ten years at Fourth Genre, won River Teeth’s Literary Nonfiction Book Prize in 2023 for her memoir, Off Izaak Walton Road: Grace that Comes from Loss, published by University of New Mexico Press, 2025. As an educator, Julier was the director of the Professional Writing Program and taught courses in nonfiction, writing, and editing at Michigan State University. Now, she resides in Iowa City with her spouse, Kate Carroll de Gutes, and works as a hospital chaplain.

Here is Megan Lutes in conversation with Laura Julier.

ML: One of the first things I noticed about your book was its organization. You have it divided into six parts, each named for a type of weather, an earth element, and what seems to be a word to reflect on, as well as a couple quotes. Can you talk a little bit about how you constructed each of these parts and why you titled them the way you did?

LJ: I started writing this book not knowing what it was about or what it would look like. I just kept writing short bits and pieces. One day, I came across a photograph of a three-dimensional art piece, a structure with dozens of small, handmade paper circles, like coins, each hanging by a string from a horizontal grid. The artist’s statement read, “I make small elements, which I join together to form a larger one. Small pieces of paper become a bigger structure.” Immediately I knew that was how I conceived of this book: small pieces that accumulate, eventually achieving a mass, becoming something else.

But I needed a way to organize those pieces to create a reading experience that made sense without merely following chronology. I knew that “what happened” couldn’t be the primary organizing structure. The most important organizing principle for me was the emotional, psychic, and spiritual shape of the story.

So I created sections and began to tease out, name, and identify the notes, textures, and one key piece of each section. I was thinking in terms of musical movements. For example, in Part I, I knew I needed to give the backstory and set the stage for the first time I lived in this cabin. But I also didn’t want this section to explain anything. It was heavily lyrical, evocative, weighted with unrelieved sadness and unspecified loss. The notes and textures are winter, chant, solitude, the river. And the key piece—the heart of it—is “Loss.”

Eventually, as I forced myself to pare down the words I chose for those notes and textures, I came up with the idea of using three words to name the primary emotional or spiritual note, to mark the orchestration that I was aiming for in each section. The first part became “Snow Fire Silence,” the second “Wind Wood Memory,” and so on.

ML: Throughout the book, place is written as both physical and emotional. What does “home” mean to you now, after living in so many places and writing so richly about them?

LJ: It’s so apt that you ask this! When I first began writing, I thought the book was about what home means, and how we know or come to feel at home. In fact, one of the pieces that I shed from the manuscript very early on began, “I grew up on an island, but what is home?” I worked with that focus for a while, but found I wasn’t really getting anywhere with it. So I backed off and narrowed my focus to the very specific things in front of me—in my hands, under my feet, what I saw and heard each day. And eventually, as those pieces accumulated and layered, and changed over time, a way of understanding home bubbled up for me. It was not something I expected to learn, and I fought it, actually.

At this point in my life, I have come to realize two things. The first is that I never was a person who was going to stay put or keep rooted in one place—never the person who would live my entire life close by the neighborhood or town where I grew up, stay in touch with childhood friends, return to a cemetery or school. I have always wandered and been drawn to the contours and differences in a landscape or town or culture. There are quite a few places on this earth that I love and would happily settle into.

The second realization is relatively new, and that is that I’m very good at creating the things that make a home wherever I am. That ability to shape space and light—which is much of what makes a place feel right to me—that ability is a gift I have also always had. What’s new is the realization that it is a gift, a kind of superpower.

ML: Much of the book grapples with silence whether that be cultural, familial, or emotional. How did writing this memoir help you reclaim or confront those silences? How has that shaped your understanding of identity, and do you think writing can bridge generational silence?

LJ: My mother was born to Polish immigrants, younger by over a decade than her brothers. Her mother died when my mother was 20, leaving her to keep house for three men and with no way to process her loss. She married my father, and was folded into his large and loud German family. I grew up with hugely conflicting messages about having a voice—what could and could not be spoken.

And just about everything I’ve written in my critical scholarly work has in one way or another been about voice and about silences. I spent a good deal of time working with the Clothesline Project, an art installation much like the AIDS quilt and the Vietnam Wall, that focuses on survivors of domestic violence. These art pieces work on the principle that individuals with a particular experience each get to “speak” their truth—in this case, writing words on t-shirts that are then hung on a clothesline, so that each person gets to speak, and collectively, the shirts on the line tell a story.

So yes, most definitely writing—of any kind—can confront and challenge, as well as bridge, generational and cultural silences. I’ve been working all my adult life, in one way or another, to break silences. Writing this book, however, was for me more about the part that comes after breaking silences. The challenge I confronted with this book was how to put words to the journey of healing, an inner journey that resists telling, resists words.

ML: Can you talk about the balance between narration and reflection in the memoir? How did you decide when to “step back” and when to let the reader sit closely with a scene or image?

LJ: As I said, I began writing not knowing at all what this book would be about—or rather, I kept trying to find the “big idea” in this book, and failing. In choosing to accumulate small bits, to focus in very tightly on the small things, I could catalog small moments of weather or light or pleasure. I also found myself writing bits of narrative, some of them stand-alone essays, some more lyric, bordering on poetic play with images. All of them seemed to fit although I couldn’t at the time articulate why or how.

But then I had all these bits and didn’t quite know what to make of them all. I would just keep writing, assuming that the meaning or connections would be self-evident to readers as well. So much of what I was trying to say felt unspeakable to me, and so the hardest work I had to do was to shape language in a way that conveyed that which was before or outside of language.

My early readers all pointed to places in the manuscript where something was missing, places where they had questions or couldn’t follow the significance. I resisted hearing that for a long time. But eventually I was able to see that those were the points where I could step back, as you say, to speak explicitly about the absence. It was relatively late in the process of revising that I came to see this: that talking about what wasn’t there, what I couldn’t find words for—talking about the fact that I couldn’t name it—was the little bit of suturing, so to speak—that would hold it all together.

ML: What do you wish for readers to know before reading your book?

LJ: I talk in the preface about the emotional ecology that I carried into my adult life. I allude and refer to wounds and trauma from my early life, some of it experienced firsthand, some of it inherited, but this is not a book about those experiences. It’s not, as one reviewer put it to me, a work of personal history or “autobiographical storytelling, summoning the past and recreating it on the page.” It’s about how deep and close attention to the particulars of one place over time changed my understanding of myself. Changed that ecology and brought me to an understanding of healing as grace.

ML: What do you hope readers carry with them after closing this book? Is there a particular emotion or insight you want to linger with them?

LJ: I’ve only come to think about this after doing readings from the book in various settings. At this point, at least, after listening to questions and responses, I would say I hope a reader comes away from the last page feeling that there’s a way through grief and loss. That it’s possible to sit with those states of being longer than they might think possible if it’s only still something imagined or feared.

ML: If you could go back and speak to the version of yourself who first arrived at the cabin, what would you tell her now?

LJ: Oh goodness. Truly, I’m not sure I would tell her anything, except that exploring and discovery is the journey, and there’s no way to point out one direction or to have a roadmap. Maybe it’s all confusing, and she feels lost, but that’s the point. Look at, dive into, and dwell in that discomfort. The way out is the way in. I’d just remind her to be mindful along the way.