By Jessie van Eerden

Cipher: Decoding My Ancestor’s Scandalous Secret Diaries by Jeremy B. Jones

Jeremy Jones seeks solid ground in his new hybrid work of nonfiction, part biography, part memoir, part detective story, part ghost story. Readers of Cipher will recognize Jones’ pull toward his Blue Ridge Mountain family land that pulses through his first memoir Bearwallow: A Personal History of a Mountain Homeland (Blair, 2014), along with the thoughtful approach to Appalachian—and American—history through a personal lens. But this new book also yearns for a narrative solid ground and the way it can make a meaningful whole of disparate parts, and for the answers to be found in genetic coding about who we are and who we might become.

When Jones learns of his nineteenth-century ancestor’s diaries written in code, he secures a copy decoded in the 1970s by the retired NSA codebreaker, Nathaniel Browder. Browder came into possession of these diaries penned in the early 1800s after a man happened upon the notebooks in a box on the curb in front of a Wadesboro, North Carolina house slated for demolition in 1975. Suspecting the diaries to be valuable, the man sought appraisals from historical societies and archivists until one archivist handed them off to the cryptanalyst Browder whose interest in history started him on a six-year decoding project that became The Enciphered Diaries of William Thomas Prestwood, purchased decades later from Amazon for eighty bucks by Jones (Prestwood’s great-great-great-great grandson).

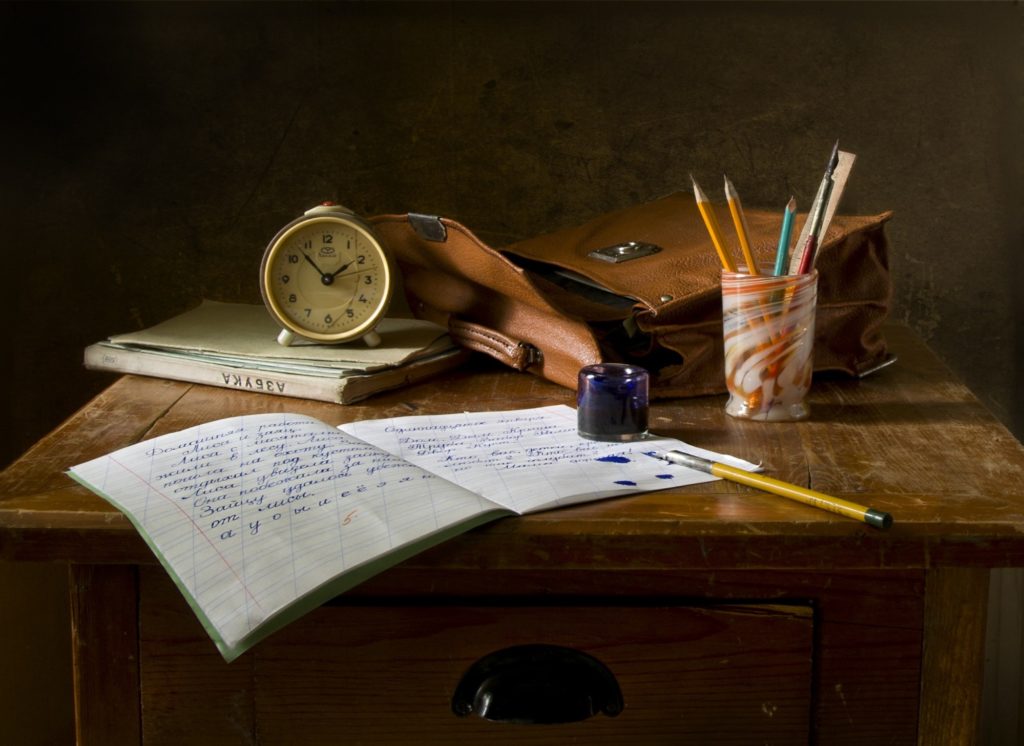

Jones soon becomes obsessed. He pores over Prestwood’s diaries in office hours between his classes, shows the dirty parts to family members like a teen, digs in archive after archive to contextualize the private life on the page, writes Prestwood unanswerable letters, spits in a tube and phones possible distant cousins while waiting to pick up his sons from school. His obsession mirrors Prestwood’s, who is fanatical for the elusive would-be paramour Mary Norwood and, later in life, for veins of gold in the North Carolina mountains. These “pathetic little books”—as Browder calls them—say nothing and everything in terse facts with no reflection or emotion. To Jones, they’re “like off-brand Moleskines,” twenty-eight handsewn books that divulge secrets of mistresses and lovers and female anatomy, but they are more log than diary, with little commentary beyond a heart drawn in the margin.

Brief spondees abound in the Prestwood logs: “Went school”; “Got sick”; “Kill’d bull”; “Housed corn”; “Hell fuss.” But such skeletal accounts give rise to invention and queries and what-ifs. Prestwood records when he gets drunk and when the snow is deep and when he meets one of his dozen mistresses in the hayloft, but he does not mention his father’s death, or the name of the child birthed by the woman he enslaves, a child likely his. Are the omissions intentional? Is the concision suggestive of shame? Jones asks, “Is the minimal black text the story and the whiteness the backdrop, or the other way round? Is what’s unsaid—what’s undone—more representative than any recorded action? Is what I can’t know more revealing than what I do? What William do I see when I foreground the silence, the absence, the negative space instead of the text?”

Much of that negative space is filled with Prestwood’s complicated relationship with slavery. Researching American slavery requires its own deciphering; Jones skillfully pieces together his ancestor’s enmeshment from archives of letters, bills of sale, court proceedings. Prestwood decidedly rejects plantation life, hides an enslaved man on the run, yet routinely rapes an enslaved woman “gifted” to him, probably fathering her four children. White Americans with roots in mountain poverty often hold to the self-righteous view that our family trees are not entangled with slavery, though being too poor to own another person did not necessarily mean unwillingness to do so, if the means had been there. We often hope backwards into our pasts, picture ancestors “on the right side of history.” Jones is honest about the ancestral story he would like to be true, and also about the mostly-disappointing story that he is piecing together. He is also honest about the murkiness of his own project and why he’s conducting it: To what extent is DNA relevant to how we live our lives? Is it instructive to know that one’s great-great-great-great-grandfather made cider and sowed oats and witnessed a woman hang? Instructive to learn that he likely sold his children?

“‘What kind of work are you doing there?’” asks a technician fixing the internet connection while our narrator studies court documents on his computer screen. Jones considers saying, “You sound like you’re from here. Who are your people? What do you know about them? About their pasts? Their sins?” Or he knows he could simply say, “I don’t know.” Instead, he changes the subject.

Cipher means not only a way to crack a code or method of coding, but also, Jones reminds us at the start of the book, a person without “weight, worth, or influence,” a worthless nobody. That’s how the NASA cryptanalyst saw William Prestwood, an “Everyman,” or a nobody that can stand in for folks on the ground at that juncture in history between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Prestwood presents himself to Jones as a cipher of all three meanings. This ancestor, in his unreadability, becomes a way for Jones to read his own life, which also gives rise to the hybrid structure of the book.

Roughly following the chronology of Prestwood’s life, Jones animates those terse lines and fills in the gaps with meticulous research, but he also dramatizes key moments in history when America is still trying to define itself, British pressures are not done with, and key events, like the slave revolt led by Nat Turner, are leading the new country toward its Civil War. These are moments that rumble between the lines of the diaries. Jones also weaves in achronological personal strands, such as his move back home with his wife and family to North Carolina after over a decade away: now he and his wife daily see people they went to high school with; they’re “feeling around for the line between intimacy and claustrophobia.” Another strand that threads throughout the book is an interrogation of American masculinity “born out of revolution.” He pulls from thinkers, such as the sociologist Michael Kimmel, exploring the self-made man. What does independence mean in an interdependent family? Is the whole point of parenting to ensure your sons won’t need you? How does one responsibly raise two White middle-class boys who are heir to privilege? Jones also decodes the eerie historical resonances between the xenophobia rampant in our contemporary U.S. (with the uptick in Confederate flags flying in his home state) and that of Andrew Jackson’s forced displacement of Native Americans in Prestwood’s lifetime.

When braiding narratives, the craft of hybrid memoir-biography-history lies in discerning between generative, illuminating interruptions and those that derail narrative momentum or splinter insight. Jones takes great care with choosing when to back away from Prestwood’s storyline to build suspense or delve into research—providing a global view of the then-new American experiment—or to make room for depicting his own memories as richly as the life of his ancestor. One sequence of chapters begins in 1812; William is in command of a volunteer militia, afraid for his life, and he seeks out Mary Norwood now married to someone else (records that day: “Sorrow Sorrow!!!” in an uncommon expression of emotion). In the next chapter, we’re with the narrator in a middle school locker room trying to pick a fight and failing. In the next, President Madison invades Canada and Tecumseh allies with the British against American expansion. We zoom out then zoom back in to Prestwood’s decision to leave his father in South Carolina and head for the mountains. Jones balances many moving pieces, gently teasing out thematic echoes. The effect: the past and present end up decoding each other.

Some of the most moving moments of the book relate to fatherhood and Jones’ growing admiration for his own parents. With a new, sleepless baby, the narrator is “stuck in a space of wanting both to become [his parents] and to need them.” In thinking about how to raise his sons, Jones also speaks tenderly of the community of men that helped raise him. Jones’ childhood was surrounded by men with a manhood not easy to categorize: “My uncles who came back from basic training with shaved heads and bruises and weapons rarely grew mad…These men could kill or not kill a rabbit on a chilly fall morning and still know something about what it meant to live in a crowded world without demanding too much space, without taking someone else’s. I knew, even then, that I ought to aim to be any one of them one day, perhaps all of them.” His grandparents also quietly shine throughout the book as models for a simple, loving life: “That striving for smallness, a life poured into the land and people around us, a life in the background, was about the holiest thing I knew.” The self is a compilation. Jones’ obsession with one philandering, daydreaming nineteenth-century ancestor ultimately makes him more attuned to the multiplicity of lives that flow into his own.

Jones doesn’t find solid narrative ground, not exactly. There are gaps and questions; he tugged at “those tattered and disconnected threads before finally settling into the knowledge that there was no knowing.” But what he knows for sure is that the threads continue. In one of his letters to Prestwood, Jones sees himself in the long line of generations—one life made up of many and, in turn, a tributary of the lives that follow—and writes: “what we can hope and pray is that when we’re laid in this North Carolina dirt, the lives we’ve passed on will understand, just a touch better, how to make peace out of thin air.” Despite not being able to find all the answers to the past, Jones can be intentional in the story he lives going forward.

Jessie van Eerden is the author of two essay collections, Yoke & Feather and The Long Weeping, and three novels: Glorybound, My Radio Radio, and Call It Horses which won the 2019 Dzanc Books Prize for Fiction. Her work has appeared in Best American Spiritual Writing, Oxford American, AGNI, River Teeth, and other magazines and anthologies. She has been awarded the Thomas and Lillie D. Chaffin Award, the Michael Steinberg Memorial Essay Prize, the Gulf Coast Prize in Nonfiction, the Milton Fellowship, and a Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation Fellowship. Jessie teaches at Hollins University.