A Study in Endurance

By James T. Morrison

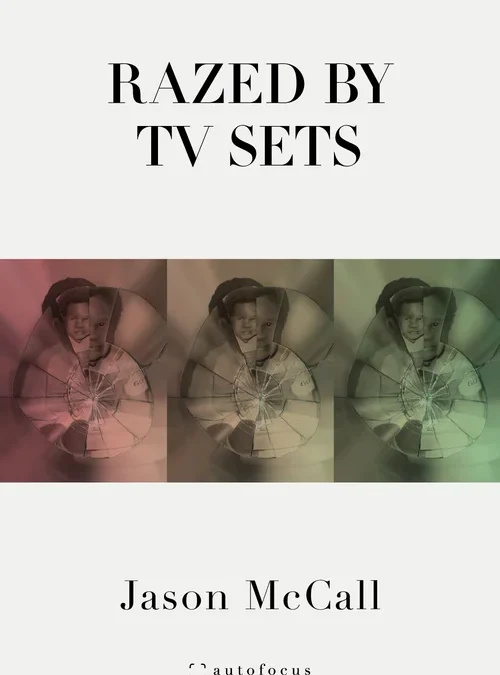

Razed by TV Sets by Jason McCall

In “My Dad Still Watches the NFL,” the opening essay of Jason McCall’s collection Razed by TV Sets, the prose is shot in bursts, every sentence beginning with the phrase “This is about,” aside from a handful of occasions where the reader is told the opposite: “But it’s not about that.” What initially seems terse and truncated moves ever closer to completion with each addition: “This is about a job. This is about how hard it is for some of us to get a job. . .This is about how it feels like we all got a good job when one of us gets a good job.” The writing continually billows and morphs, expands and contracts. McCall returns to this technique repeatedly throughout the collection; what begin as shallow breaths become deeper and more meditative with each iteration. Stylistically, it is no surprise that the author would employ anaphora, given his background as a poet with several collections to his name. Still, the foundation of McCall’s first book of prose is built on repetition, and yet nothing about it feels repetitive. Instead, the tactic acts as a compass, a way to navigate through seemingly antipodal content, a needle always pointing toward some broadly specific version of the truth.

The collection is, ostensibly, about popular culture. About celebrity. But really, each essay provides a new lens through which to view all kinds of subject matter, perhaps none more than illness, aging, and death. McCall also uses celebrity in an uncanny way here, as the famous folks who grace the pages of this book are not lathered in praise for their apparent greatness, but rather lauded for their tenacity, their grit, their willingness to live to the fullest, even—as is the case with WWE wrestler Eddie Guerrero—to their ultimate peril. But this is not just about McCall’s fandom of legends and underdogs from the NBA, or the NFL, the WWE, or the music industry. It’s about how these subjects intertwine with his own unraveling, trips to the psychiatric unit brought on by those nagging thoughts of suicide some of us know too well. It’s about the author’s own struggle to make sense of a world where nothing makes sense. And yet, he draws lines between disparate ideas in a way that turns the nonsensical into logic.

I generally try to leave myself out entirely when discussing another author’s work, as my ability to relate (or not relate) with the material is usually of no consequence. But I believe it’s somewhat relevant to note that I, too, have been locked up in psychiatric facilities for suicidal ideation and behavior. McCall’s essay, “The New Transported Man,” is easily some of the best writing on the subject I’ve ever read. Like the rest of the book, it is authentic and unflinching. Suicide is a fraught and frightening subject most people avoid, but it requires deep consideration for those of us who don’t have that option. McCall sums this up in one perfect sentence: “My mind is divided on suicide in the same way some Christian denominations are divided on the idea of sin.” What follows is an opening into the author’s experience with what he calls a “second birth,” and in a text riddled with dates by a person who seems obsessed with them, the author writes: “November 13, 2005. That’s the only day that matters and the only day that will ever matter for me.” That’s the day McCall decided not to kill himself.

One of the most remarkable features of this book is its author’s ability to tie threads between himself and the stars highlighted, shedding new light on both his own experience and that of the celebrity. For instance—had someone asked me what I thought of Lil Wayne’s fifth album in Tha Carter series, I would have been honest: I never listened to it. I truly enjoyed Wayne’s earlier work, but he had become a punchline on the internet, and so I (wrongly) assumed his later music wasn’t worth listening to. This is, in part, the impetus for the essay “Tha Carter V Means the South’s Not Dead, Either.” While the world pokes fun, the internet abuzz with punchlines about the aging artist’s choice to tour with pop-punkers Blink 182, McCall comes to his defense—only not in the expected, ‘he was a legend in his day’ kind of way. Rather, McCall finds something truly noble in Wayne’s attempt, as the artist hunts for—and finds, according to the author—some earlier version of himself. The piece is so compelling I gave Tha Carter V a true listen, and he’s right: it’s full of great flows and personal storytelling, much like Wayne’s earlier output. But convincing the reader of this does not seem to be what McCall is ultimately after. “Wayne is still alive,” he reports. That alone is something to cherish.

Wayne’s journey toward reclaiming himself represents one of the book’s most revisited themes: work. The work it takes to grapple with massive existential questions; the work it takes to simply exist as a Black man in the United States. In “Oscar Grant’s America,” an essay that surrounds the film Fruitvale Station, McCall writes, “The movie is a study in endurance, and endurance is an American virtue. . . However, endurance is more than a virtue in the black community. Endurance. Grind. Hustle. They’re just different names for the god worshipped in ‘We Shall Overcome,’ Sam Cooke’s ‘A Change Is Gonna Come,’ and Tupac’s ‘Changes.” The author goes on to examine the impossible position that America’s inherent and structural lie of equality puts the Black community in, especially the double standard applied to young Black men. But as the piece closes, McCall shifts focus, highlighting a tender moment while exiting the theatre; he and two young men who “could have been cover models for a Bill O’Rielly op-ed on wild black boys” hover, for just a moment, in that liminal space reserved for vulnerability. For grief.

There is an ineffable quality to this book that I have been trying (and failing) to put my finger on; the word “nuance” kept coming to mind, but language that vague and overused doesn’t cut it. Fortunately, McCall has no shortage of prose that captures what I’m grasping for: “Honest people make the best liars. I am a very honest person. I am a very good liar.” This is, on its face, a contradictory statement. And yet, by the end of “The New Transported Man,” it doesn’t feel like a contradiction at all. The book is predicated on the often-contradictory nature of existence, on honesty, on structural lies and unwitting lies and personal secrets, on trying to sort and differentiate one from the others, all while acknowledging that “even the truth is its own type of fiction.” The steady beat that drives this book is built on an acknowledgment that “the truth” often requires amendments, as do so many things. That’s what Jason McCall manages to do in myriad ways in this fabulous collection—amend sentences, concepts, truth, memory, and legacy, while leaving room, when the need inevitably arises, for future repairs.

James T. Morrison is a writer and visual artist based in California’s Central Valley. He currently serves as both the managing and nonfiction editor for The Normal School literary magazine. James’ essays and visual works have appeared or are forthcoming in Slate, Diode, River Teeth, and Fugue. You can hear him talk about his writing and drug policy on the award-winning podcast Death, Sex, and Money. To contact James, or see more of his work, visit: www.james-t-morrison.com