By Tarn Wilson

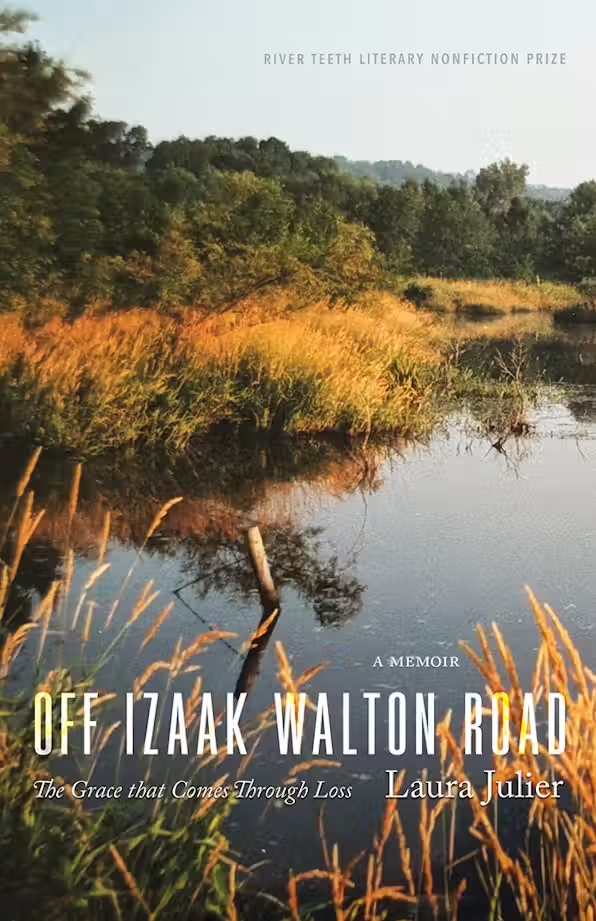

Off Izaak Walton Road by Laura Julier

Twice Laura Julier has fallen deeply in love—with a place. The first is a small Iowa City home with a lush yard where she lived for eight years. The second is the focus of her memoir Off Izaak Walton Road: a small patch of land and ramshackle cabin on the Iowa River. The eccentric owner lives part time in Belize, so invites Julier to make the place her second home. For seven years, whenever Julier has a break from teaching at Michigan State University, she makes her pilgrimage. The book traces her love affair from love-at-first-sight, through the deep attachment, to complication and self-examination, to letting go–and in the process invites readers to examine their own psychology and relationship to place and to loss.

The first time Julier’s car bounces down the gravel road and she sees “a blue one-story dwelling nestled deeply among the gardens and groves” (20) surrounded by low rock walls and walnut, oak, sycamore, juniper, hemlock, and white pine, she is smitten. Not only is she struck by the charm and beauty, but she feels “rooted and grounded,” able to “breathe more deeply, uncurl, unfurl in my own skin, into the place around me, a freedom I have not known before” (25). Even though the landscape is far from her New York City childhood, she writes, “I knew myself to be home” (5).

Much of the book is a celebration of her beloved, rendered in intimate detail. She catalogs the quirky items in the cabin: a butterfly collection, a 1944 calendar, a 19th century photograph of a woman in a long white dress sitting on a wall. She keeps a nature journal and an ever-lengthening record of birds she can identify. She shares moments of connection with birds, especially owls and eagles. She researches the local animals, recording their habits and life cycles. Like someone piecing together the story of a loved one’s past, she scours old documents to learn the history of her little bend of the Iowa River and traces its ownership and lineage all the way back to prehistoric times.

Julier also shares vulnerable, almost mystical moments of transformative union. One spring, when she first arrives for a stay and opens the car door, she is unexpectedly washed by overwhelming, unprocessed emotions. But when she steps into the space, she feels “safe under the sky to open my rib cage,” and her “long-held, well-tended self-protecting membrane thins.” She begins crying, “exhales into the wide spaces.” She continues:

And in that loosening, in that spilling, in the opening, it is as if an equation finishes, balances. Yes, there are old wounds I carry, but instead of curling in upon the pain, tightening and protecting, withdrawing, I follow it, expanding moving swelling into the space here, and it dissipates, rising with the heat. There is no one here, no intrusion, no fear, no long-ingrained impulse to draw, withhold, subdue. It is rising, my breath rises, I spread my arms, raise my gaze.

And there above me, of all the spots in the wide open sky, exactly above me, three red-tailed hawks are riding the swelling, rising thermals. (132)

Julier’s rhythmic language, her choice to leave out the pause of punctuation in “expanding moving swelling” reflects the ecstatic nature of her union. Her love affair, which has melted the barrier between self and other, offers her a place of connection and safety which gives her the gift of emotional release and transformation.

Julier is by nature mystical, but she is also a trained academic, a skeptic, a questioner, and she begins to wonder if her relationship with place has an unhealthy dimension, a clinging that echoes past codependent relationships. When she must return to Lansing, she is “bereft” (29), with a depth of grief at the separation that other people find peculiar. She surmises that her attachment may be rooted in a traumatic childhood. She keeps the specific details of her past private, but we know that she has experienced neglect, betrayal, and abuse—and found sanctuary in any wild spaces she could find at the edges of her urban and suburban neighborhoods. People were dangerous; nature was trustworthy.

Midway through the book, she recognizes she may have idealized her beloved. A friend who comes to visit Julier’s paradise comments that “it feels a little like the site of some sort of industrial accident” (162). Julier sees the landscape through her eyes: “Sand and gravel pits, a field of recycled cars, two concrete plants, a river lined by trees with their tops sheared off. It’s not pretty” (163). She admits to the reader that Izaak Walton Road is often littered with trash and the Iowa River is indeed polluted.

There are other complications in her relationship. Julier is a lover–and rescuer–of all small creatures, yet she can’t save all the snails and turtles from being crushed by barreling pickup trucks or the frogs who die from a mysterious ailment. Her cold and crumbly cabin is filled with insects and mice. She can’t prevent her cats from killing those mice, nor live at peace with their deaths. She traces this, too, back to her childhood, recognizing that in her obsession with protecting little animals, “I am caring for the small, the vulnerable, the wounded part of myself” (179).

Her intense attachment might also echo generational losses. Her grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, then Eastern Poland. When the family transplants into the mishmash of the New York melting pot and has to focus on survival, they have no capacity to grieve what they have lost: “My mother would not talk about the land her parents left to come to the tenements of New York. Would not even entertain the idea of making a trip to find out. Would not acknowledge until I was an adult that she knew the language, remembered its cadences and vocabulary from childhood. How much I wanted her to teach me something other than how to cover loss with shame and silence”(6). Julier’s despair at separation might partially be her family’s unresolved grief at being stripped from their homelands.

Ultimately, her love affair comes to an abrupt and unexpected end when the owner of the cabin, a solitary and erratic person, prohibits Julier from returning. For a time, Julier returns to secretly observe from a distance. Over time, though, she recognizes that the place has taught her how to let go. Over the years, she has watched species thrive and disappear, seen the land carved by storms and floods, researched the way the Iowa River had changed paths over eons. She realizes “that there is a life cycle for a place, for an ecosystem, and for individuals . . . Everything had changed, and I with it” (262).

In the end, it was not the physical place alone that had transformed Julier, but her relationship with it: her openness, her attentiveness, her capacity to love. “I’d been holding on as if the place is what had kept me rooted and grounded, as if the place itself had been the source of any joy” (262). She would take what she had learned with her and share it with others—both with her writing and in her new career as a hospital and hospice chaplain. “I needed to return to the lessons of paying attention: it was walking the road day after day, the sensory attention of sight and sound, the face-to-face encounters that taught me” (263). The gift of time immersed in the natural world in which her rhythms were in tune with natural rhythms, of daily walks and chores, of paying attention with all her senses, of connecting with other species—all this had returned her to herself.

Tarn Wilson is the author of the memoir The Slow Farm, the memoir-in-essays In Praise of Inadequate Gifts (winner of the Wandering Aengus Book Award), and a craft book: 5-Minute Daily Writing Prompts. Her essays, poetry, and reviews have appeared in numerous literary journals, including Assay, Brevity, Gulf Stream, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, One Art, Only Poems, Pedestal, Potomac Review, River Teeth, Ruminate, Sweet Lit, and The Sun. She is a graduate of the Rainier Writing Workshop and an educator in the San Francisco Bay Area.