By Seth Kaplan

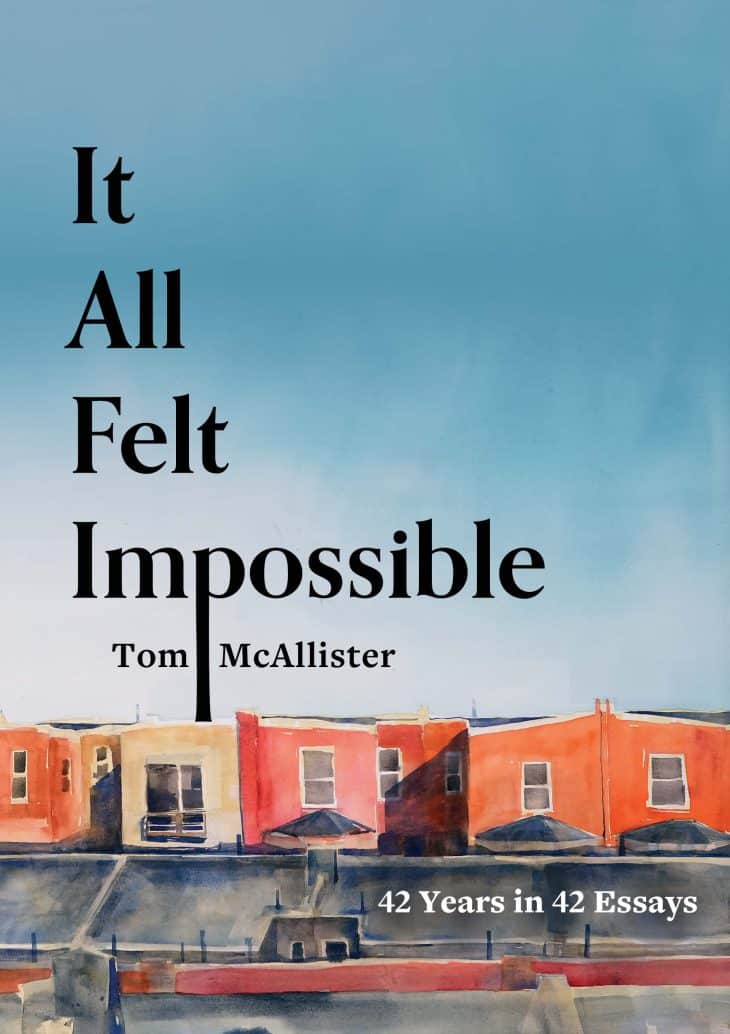

It All Felt Impossible: 42 Years in 42 Essays by Tom McAllister

It’s 12:15 a.m. and about an hour ago, I told my iPhone’s bedtime reminder to take a hike because I had to finish the last thirty pages of Tom McAllister’s remarkable memoir, It All Felt Impossible: 42 Years in 42 Essays. The book is a collection of crisp life memories – each essay no more than 1500 words, all with acres more land to cover if McAllister were flowery or long-winded, or, if he were paid by the word. A master sentence-maker, McAllister packs such punch into each of the book’s essays, that you need a minute (or fifteen) to pause at the end of each, just to be sure you caught every detail, and to think about the woven connections from essay to essay and year to year. And perhaps most critically, to consider what the details of his life story tell you about yours.

Naturally, since McAllister is a decades-long writer and professor, It All Felt Impossible spends much time ruminating on the writer’s life. This starts straightway in his Author’s Note. Readers tend to skim Author’s Notes, but this one is an essay of its own: not a dedication or disclaimer but a direct address explaining how, due to a scheduling glitch, he had two novels: The Young Widower’s Handbook and How to be Safe, published within thirteen months of each other. He acknowledges that all writers should all have such problems, then shares the vulnerable truth that afterwards, he stopped writing. This is a fact that many writers won’t acknowledge; we readers are to believe that the words flow easily and always from published authors. After months, McAllister pivots to his role as a writing professor, chastising himself for not following his own advice to his students when dealing with “writer’s block.” He sets out the specific constraint to write an essay a day, 1500 words, no more, no less, himself the teacher and the student. The result is this collection.

While the essays in It All Felt Impossible in are titled by year in chronological order from McAllister’s birth year to the year of publication, their content doesn’t technically work that way. While the narrative traverses his memories of childhood – loving G.I. Joes, professional wrestling, and his time in AOL Chat Rooms, to adulthood, including professional struggles, his wedding, learning to ride a bike – the narrator’s connections and inquiries into events rarely confine themselves to that singular year. The book is not linear because McAllister is telling us that life is not linear, and that everything is all mixed up and most often, it feels impossible not only that all of these things happened, but that they all happened to him: small moments in an order that, while organized by year, superimpose one another in a way that cannot be held by any container, or neatly packed into convenient piles. That’s the life that McAllister guides the reader through. At once tender and unflinching, we learn of McAllister’s private terrain of panic, self-discovery, cultural critique, and love. The essays remind us that growth often comes through missteps, that memory shapes identity (whether you like it or not), and that meaning must be reimagined when life feels unfathomably wide and uncertain.

In “1982” (the year McAllister was born) a year that is, obviously, without real memories, he writes about his wife LauraBeth – born in the same year. Of course, they did not know each other then, but “her birth is the event that shapes everything that follows,” a line that plants the seed of his most important relationship and at the same time anchors the collection in both nostalgia and intimacy. The rest of the book is indeed an ode to LauraBeth; with subtlety and grace, McAllister write about his spouse with honesty and reverence. His life is owed to her, and he hints that it might have ended up very differently without the serendipity of their meeting, and the rest of the collection follows. She’s calmer, less competitive, and more grounded but not painted as a fantasy, as can happen when writers wax rhapsodic about their partners. She asks pointed, loving questions, which serve as foils to McAllister’s own constant anxious inquiries.

As a reader, we’re happy she’s around.

In “1988” McAllister tackles his childhood and his path to the present day all at once. He remembers a time that his grandmother took him to the zoo, a poignant glimpse into his childhood where polar bears were his favorite animals. That very day a tragic accident occurs. In the aftermath, his grandmother walks him away from the rescue vehicles to a zoo map, and points to the small red cross. “‘This is where people like your mom work,’ she said. ‘She makes sick people better.’” The memory then becomes not about the accident, but about the medical and emergency services that would help the victims. Juxtapositions like this are the crux of It All Felt Impossible. In perhaps my favorite paragraph in the book, McAllister writes about first responders, not only as brave and fearless, but as skilled tacticians that exhibit “extreme competence.” And in his own segue to cultural criticism, McAllister writes, “if our movies celebrated heroism as the culmination of a life of patient and thoughtful practice, rather than random miracles performed by angry men, we would be an overall healthier society.”

In “2013,” the essay I was reading when my iPhone told me to stop, McAllister tackles feeling invisible through a tiny memory – leaving a family gathering to get more orange juice for mimosas. When he returns to the party after his errand, it’s as if he was never gone. He wasn’t seeking “balloons and firecrackers” upon his return, just some acknowledgement, but there was none. A microcosm of his own insecurities, McAllister ends the essay stating, “It’s best not to think about some things for too long,” which evokes both his vulnerability and his coping mechanism, here and in the entire book. The same is true in “2005,” when McCallister ruminates an old TV that he takes to the dump and how it will “outlive him by a million years,” and the several occasions in the book where he discusses his writing life, and whether he has anything left to offer or had he “used up all the good words in his system.” He has not.

The phrase a “writer’s writer” is overused. But McAllister fits the bill. It All Felt Impossible does in 160 pages what takes most writers reams to produce: a rigorous examination of the intersections of memory, vulnerability, and revelation. By depicting the cycle of failure, recovery, and transformation, it interrogates how identity is continually renegotiated in relation to both external forces and interior experience. McAllister shares with us his life and by doing so, leaves no choice but for—at least this reader—to peek into his own.

Rose Metal Press

$16.95 Paperback | Buy Here

Seth Kaplan is a writer and attorney in Evanston, Illinois. When not lawyering and writing, he coaches baseball, practices yoga, and raises tomatoes. Seth is at work on a to-be-named essay collection about his lifelong (sometimes serious but often comical) quest for existential permanence, and a novel. See more of his work at www.sethkaplanwriter.com and follow him on Instagram @sethkaplanwriter.