By Zosia Paul

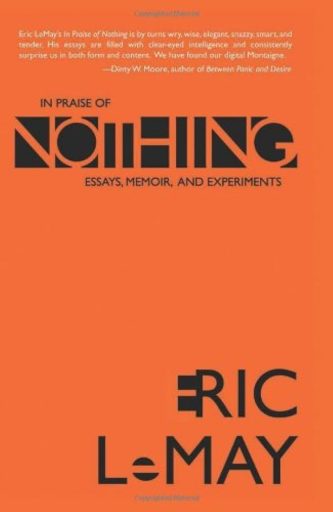

The Translator’s Daughter by Grace Loh Prasad

Grace Loh Prasad’s debut memoir, The Translator’s Daughter, both tenderly explores the death of loved ones overseas, and the precariousness and ordinariness of living as a third-culture kid. Prasad details her struggle for belonging as an itinerant woman, trying to maintain connections to her culture and language while still creating a life of her own in California.

Prasad’s memoir narrates an intricately complicated bicultural childhood. She was born in Taiwan to a large extended family, but political tensions with China forced the family to emigrate to America when Prasad was still a toddler. Her parents returned to Taiwan after she graduated high school, and she never again lived in the same country as them. Their reconnection with Taiwanese family and culture versus Prasad’s disconnection and distance lead her to interesting epiphanies about language and community. She grapples with the guilt of not living closer to her parents, especially as they age, but notes the difficulty of potentially living in Taiwan because of the language barrier. She admits to anger over this divide in her life and points out that she was in this position in part because her family’s move to America hadn’t been her decision. To compensate for these feelings of isolation from her homeland, Prasad finds herself depleted years later in California; she overextends herself as a literary citizen and her friends’ social organizer, and realizes it comes from needing to feel secure in a community. Without a family structure, she must initiate community for herself. These epiphanies act as a balm to readers also navigating competing identities.

Prasad makes a powerful creative decision to start her memoir with her experience of being stranded in the Taiwanese airport with an expired passport on a family visit, because it emphasizes her feelings of dislocation from the Asian diaspora. She must procure an updated American passport to Taiwan within twenty-four hours, or she will be sent back to the States. Though she feigns belonging with her appearance, she can barely communicate with the airport employees around her for help—she can’t write something as simple as her dad’s name. The tense airport scenes and Prasad’s frequent apologies represent the feeling of limbo that she describes living with her whole life as an “accidental immigrant.” Her willingness to sit with difficult questions and reveal her embarrassment and sadness over the language barrier echoes beautifully across the whole book. She returns to the airport in chapter four, “The Year of The Dragon, Part Two,” after two standalone essays, thereby teaching readers that the book requires they make connections just as Prasad must. The memoir’s mixture of traditional narrative writing with formally experimental essays (a list, a letter, etc.) suits Prasad’s hybrid life. In the airport chapters especially, Prasad’s thoughtful outlook goes beyond an in-the-moment struggle with isolation to elevating the memoir’s main stake: losing her parents who translate for her and connect her with her relatives, language, and knowledge of her hometown, Taipei.

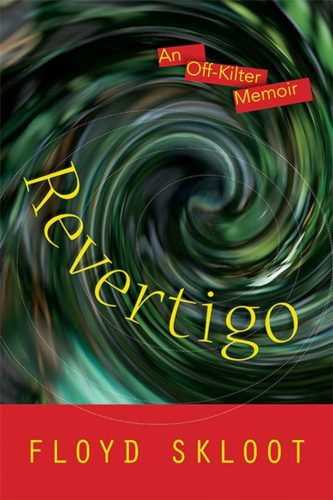

As the memoir progresses, so does the physical decline of her family members’, all the more tragic because Prasad becomes further isolated. She slows down time in the scenes when discussing final care decisions for her parents: her mother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis changes her personality, and this is reflected through the more deliberate pacing. The measured movements in these sections help the reader understand how much Prasad’s life will change. Prasad’s father, the fifth of ten children of a Presbyterian minister and missionary, was fluent in four languages before he received his PhD from Princeton Theological Seminary. He became an expert in Bible translation—language was his trade—so it’s particularly tragic when Parkinson’s diminishes his ability to speak. Though surrounded by family while visiting him in the hospital, Prasad stands as the lone English speaker. At one moment, when he strains to communicate with them, Prasad notes, “As the translator’s daughter…I never had to worry about being stranded. But what happens when a translator can no longer speak?” Not only is she losing her family, but she also struggles to be in another country while grieving. After attending family events in honor of her father, she returns to California and notes, “I felt untethered and off balance, trapped in a strange world where everything looked familiar but nothing was the same.” Her memories of her parents are from another time and place, and the people in her day-to-day life don’t know them, making her grief feel like a painful secret.

Prasad adds further depth to this memoir by finding refuge in art as she makes sense of the ever-evolving complexity of her identity. Decades before her parents die, as a young adult in California, Prasad attends a screening of the documentary First Person Plural. The film centers on an adopted girl who discovers that she wasn’t actually an orphan after finding her birth family in Korea. Prasad realizes that she, like the main character, lives with the sorrow of the life unlived that exists in the shadows of the one she was thrust into. It was a unique revelation that was brought out through her personal affinities with art.

It was only after many years of identity struggles and family deaths that she is able to reconcile with the direction of her life moving away from her family to create art alone. The two aspects of her life being mutually exclusive is explained through her comparison of the goddess Inanna, and her legendary journey to the underworld that ended in the reversal of her death. Prasad describes the heartache of knowing her own tragedies have no undoing. She reckons with her only option being to honor her life and lost loved ones through her artform of writing, as no earthly thing could reverse her pain.

It is through her writing that Prasad leaves readers with powerful conclusions about home and belonging. The memoir is a reminder of the beautifully complex insights that result from extensive self-discovery. Despite the added psychic distance accompanied by the death of her parents, Prasad reaches an understanding and acceptance with her new life in California and relationship to Taiwan. Building toward a conclusion, Prasad notably remarks, “My husband and son are in California, but some part of me will always belong to Taiwan. This eternal ache is what it means to live in diaspora. Home, for me, is not an answer but a question.”

Zosia Paul is a junior at the University of Tampa, majoring in political science and minoring in writing. She works as a research assistant for on-campus projects and holds executive board positions in University political clubs.