Feral Youth, Fast Cars, and Fraught Love

By Brandel France de Bravo

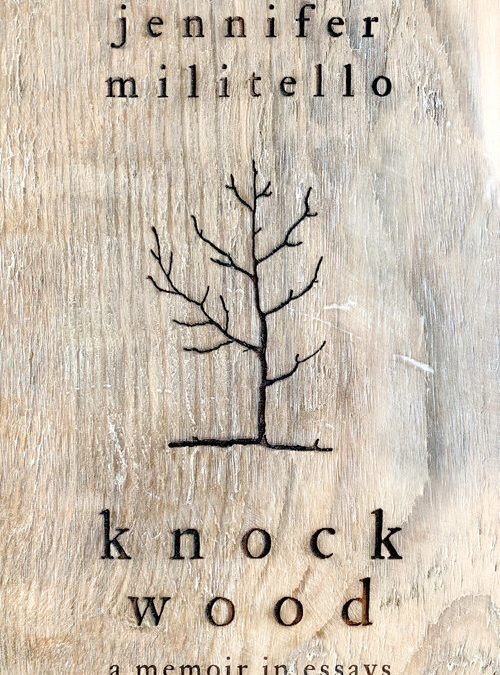

Knock Wood: A Memoir in Essays by Jennifer Militello

While billed as a memoir, Knock Wood, winner of the 2018 Dzanc Nonfiction Prize, is more akin to a theme-and-variations composition: Think love-child of early Bruce Springsteen and Bach’s Goldberg Variations. An acclaimed poet, Militello tells her story in twenty-nine discrete essays that mostly eschew chronology. There isn’t just one title essay but five, each about a lover named Tim and the nature of time, which in Militello’s metaphysics includes a future that “might influence the past.”

In the first of the five title essays, which are interspersed throughout the book, the married-with-children author meets Tim for their first tryst. When he shows up at the train station, Militello glimpses her future and perceives action and reaction occurring in reverse order:

I knew I’d leave my marriage. I knew I’d regret it and die crazy. But none of that could be helped. The arrow points both ways…You knock on a novel instead of wood and it kills someone in the past.

It’s fitting that Militello and her lover meet at a train station, a locale that nicely telegraphs the book’s principal themes: 1) the uncanny nature of time that runs in two directions like a double-track railway; 2) the way our origins—where we’re raised, our family—always lie beneath us like train tracks (one relative attempts suicide by jumping in front of a subway); 3) the desires that carry us away, rendering us passengers in our own life. Bob Dylan wrote: “It takes a lot to laugh, it takes a train to cry.” Jennifer Militello writes: “The only way we knew love was through hurt. We gave each other the gift of harm.”

The five essays titled “Knock Wood” form a circular narrative through time analogous to the rings of a tree. The fifth one depicting the end of the author’s relationship with Tim begins, “In the end, I recognized that the train approaching was not the one that had dropped me off.”

Some readers associate the label “memoir” with a unique life-story or hardship, perhaps the sensational or salacious. The memories that overtake Militello like an invasive species (one essay about memory is titled “Invasive Species”), and the difficulties she bears witness to, are what we’ve come to view, sadly, as ordinary: a high school boyfriend who dies from a heroin overdose, an abusive uncle, post-partum depression, an aunt and uncle with mental health issues, marital infidelity. Rather, it is Militello’s writing—the range of styles, perspectives, and lyrical language (“We turned each other inside out. We were mollusks with softness of organs for shells”)—that lifts this book out of the ordinary, making it unpredictable and exciting.

As is typical of memoirs, Militello mostly writes in the first person. But in at least three essays she uses a different point of view to emphasize the distance between the narrating self and experiencing self (second person in “Why I became a Criminal” and “Procedures for an Outing,” and third person in “All the Resonance of a Smashed Violin”). But more striking is her deft use of the passive voice in “The Problems of the Mothers,” “The Living Room,” and “The Accidents,” to convey inevitability, helplessness, and neglect. About her grandparents’ home, she writes:

There were rubber bands on the door handles. No one used them but there they were, stored up, red, green, dun-colored, for the day they would be needed. Clusters of rubber bands, rows forearm-thick were they to be placed around a wrist. Things wanted to be bound or joined but instead the rubber bands stood as markers, like lines convicts scratch on cell walls to track the days. Nothing was held together. Nothing was wrapped or sealed or glued or welded or screwed. There were no clothespins. There were no paper clips. There were hardly hinges. Nothing was ever given a Band-Aid or tied up with a string.

The above excerpt also highlights Militello’s ear and ability to craft a sentence as a poet does the line: the internal rhyme of “glued” and “screwed” and the series of four-word sentences beginning with “There were,” which hammer-home the lack of ties that bind. Such repetition and anaphora structure her writing musically. There are, for instance, whole paragraphs in which every sentence begins with “like” or “because.” (My only quibble about her style would be the liberal use of “like” throughout.) If repetition can be considered a vocalized pause, Militello demonstrates over and over again her desire to stop time in its tracks.

As a poet and essayist, I am a fan of Militello’s brand of nonfiction, where moments, images, feelings, and thoughts are on equal footing with action. Without an arc or obvious plot points, which can seem contrived in a memoir, hers is a different approach to story-telling. The “story” takes shape through accretion. What was less convincing for me structurally, and occasionally felt like an artificial through-line, were her regular references to bi-directional time, wormholes, and the superstitious practice of knocking on wood (she even wears a wooden ring). These references aren’t limited to the five “Knock Wood” essays. In the opening essay “Theory of Relativity,” for instance, she attributes an uncle’s death three years earlier to knocking on paper and “felt that ill-fated knock travel back in time.”

What I love most about Knock Wood, Militello’s first foray into nonfiction, is her vivid depiction of adolescent life in working-class neighborhoods and her portrait of a New England mill town. The youth are feral, the adults mostly absent and sometimes malevolent: “Her father’s wife is the kind of woman who pinches a child when no one’s around just to see what the child will do.” “The Town” is so gorgeously written, spot-on, and evocative, I wish everyone would read it, particularly now as we try to understand what we’ve become as a country.

Here are selected passages from the last two paragraphs about the boys of her town, some of whom she loved and have already died, who drink and drive “late at night at top speeds through winding wooded back roads with the headlights off and the music turned up; it almost kills them and it keeps them alive”:

What can any of us know of their lives? The sons they are, skinny in their belted jeans, heads hung and long arms, what do we know of their starved kittens and unpaved driveways and widowed mothers and diseased dogs? What do we know of their bedrooms, mattresses without sheets, fridges without food, sugar the one thing on the shelves, the one broken chair in the kitchen in which they sit and then lean too far back?

Love them and they will be dust that sifts through your fingers. Love the damaged, the despised, the crooked, the lost. They are your boyfriends, your friends, or your fathers. Love them and this is what you get.

Militello has created “a gift of harm,” inflicted and received—a way to look at and love what is broken—and for this I am immensely grateful.

Dzanc Books

$16.95 Paperback | Buy Now

Brandel France de Bravo is the author of two prize-winning poetry collections (Provenance and Mother, Loose), co-author of a parenting book, and the editor of a bilingual anthology of Mexican poetry (Mexican Poetry Today: 20/20 Voices). Her poems and essays have appeared in various publications, including Alaska Quarterly Review, Cincinnati Review, Fourth Genre, The Georgia Review, Green Mountains Review, Gulf Coast, and the Seneca Review. She holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College’s low residency program for writers. You can read more about her at www.brandelfrancedebravo.com.