What’s Hidden Beneath

By David MacWilliams

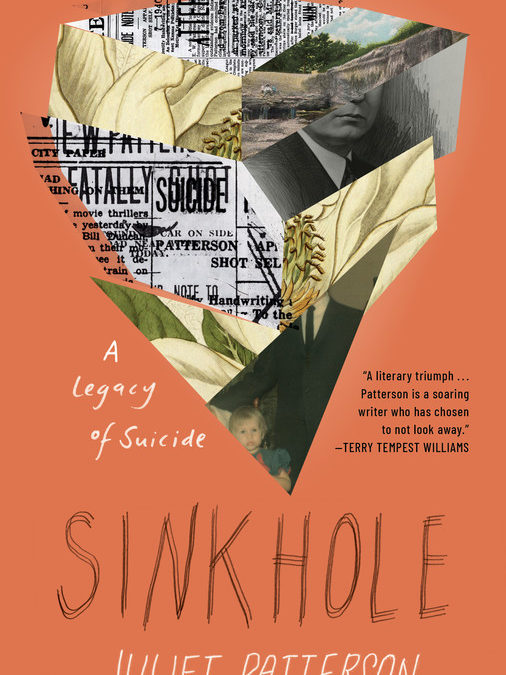

on Sinkhole: A Legacy of Suicide by Juliet Patterson

Her father’s suicide in December of 2008 leaves poet Juliet Patterson in a state of grief and bewilderment. To understand his choice, she begins to mine her family history—both her grandfathers also died by their own hands—and the history of the men’s shared hometown, Pittsburgh, Kansas, as well as the region around it, Crawford County, a place where abandoned coal mines pockmark the landscape with sinkholes. In her memoir, Sinkhole, Patterson explores the potential causes of the suicides in her family and the links between suicide and the historical moments, geography, and personal lives that are inextricably bound to one another. Her project, however, develops into an exploration of the responses suicide creates in survivors. Her memoir is grounded firmly in strenuous research, honest assessments of family members, and a narrative style that is intimate and engaging.

To better understand the legacy of suicide in her family, Patterson brings to bear the skills of a researcher, interviewer, and poet. In the most moving passages in the book, she imaginatively recreates the final hours of each suicide to better convey the human anguish. Her approach to the topic, though, is broad. She examines the familial and public archives of both sides of the family, interviews family members and historians, and reads countless newspaper articles and treatises on suicide to understand why the men in her family killed themselves. Why do people choose to end their lives, and what influences, if any, might the current history and the geography of place have in such decisions? She also learns about the reactions of the survivors in her family and how each in her or his way avoided facing the suicide.

The suicides in her family surprised the widows and family members left behind. The men planned their deaths in silence—and that silence lingers. The wives of the deceased grandfathers avoid discussing their husbands, just as Patterson’s mom is also inclined after her husband James dies. Patterson raises the topics of erasure and reticence repeatedly. For instance, she reflects upon the silence her parents maintained over their fathers’ suicides. “If we rarely talked about important things,” she writes, “it was next to never that I heard them discuss their childhoods or my grandfathers.”

She recovers the lost pasts of the dead men because she recognizes that their deaths haven’t erased them. In her poem “Dark Scaffolding” from her collection entitled Threnody (Nightboat, 2016), Patterson’s speaker muses on the passage of time and on the presence of that past. “Things have already happened / before we were here. That was now.” The sentiment behind that last phrase, “that was now,” resonates throughout this memoir. She reminds us that while the past had its immediacy to those who lived it, the consequences of the past don’t go away. Even if past actions are not discussed, their impact remains.

Patterson laces her memoir with imagery that is stark and real. She interrogates what she observes. Patterson and her mother go to view the father’s body for the first time at a funeral home the day after James, her dad, hung himself. A fraught few minutes pass as the mother paces before the body, demanding to know why. Patterson stays with her father’s body after her mother leaves the viewing room.

With my mother out of the room, I felt more relaxed, despite the difficulty of the moment. I stood up and moved close enough to touch the body. His hand first: cold. And then his head. He was gone. He did not exist. A feeling of immense sadness that I could not control welled up and caused me to emit a strange sound, something like a sob. I studied his face. His mouth twisted in a small grimace, and there were still traces of what I can only describe as determination across his brow. It struck me that I had seen hints of this expression in him many times before, though never so precisely. I closed my eyes for a moment. An image of a noose appeared, as though lying in wait. I opened my eyes. Without thinking, I lifted the cloth away from his neck. I had an impulse to know in more detail the circumstances of his death, to understand in clear terms the consequences on his body. The worst had already happened, so why not face it as best I could? Later I read the coroner’s report and learned the marks were consistent with two separate ligature furrows, with two individual nooses. It was a gruesome sight. I covered him as quickly as I could. I heard myself mutter I’m sorry in an audible whisper, not so much an apology as a groan. I stepped out of the room.

Besides the stark imagery, Patterson employs extended metaphor and symbolism throughout the memoir to link her topics. Plastic bags and boxes are filled and emptied; common place items like duct tape, a pocket knife, a wristwatch, and receipts suddenly emerge as significant, haunting artifacts; notes are left behind; family photographs are examined in ekphrastic passages where memory and imagination meld; road trips are taken, sometimes without return. The most striking metaphor of all is the sinkhole.

In Patterson’s memoir, sinkholes are metaphorical—vast spaces of emptiness that we’ve created, and that inevitably rise from below, revealing old damage and creating new damage when they emerge, like unspoken secrets no longer silent. Patterson makes many trips from her home in Minnesota to her parents’ hometown in Kansas. On one trip she drives over to one grandmother’s former house just to have a look at the place, and she’s stunned and frightened by the sinkhole she encounters across the street. She finds a house cordoned off that has been moved from its foundation in the yard to the sidewalk because its “basement [was] crumbling into a gaping, cavernous sinkhole.” The image is alarming, and it becomes the seed for the extended metaphor of sinkholes Patterson uses in her book.

The hole was frighteningly deep. From where I stood, it looked as if the lawn had been punched with a massive awl, exposing the ground’s secret interior. A mass of shrubs had been pulled into the void, littering the rim with branches and leaves, while broken concrete, pipe, and wire beetled everywhere. I had never seen anything like it. The terrifying, alien world of a sinkhole—the earth turning in on itself—an obvious metaphor. One I couldn’t ignore.

That morning, staring at the hole, I felt as if I was looking into a realm that I could not enter. A world of dark earth, of broken rocks and minerals, of air and water, all the things that had always been there and would always be there—but which we don’t very often consider, and the sight of which, for some reason, made my hands tremble. I looked down to see the fencing tremble, my fingers wrapped in its mesh.

Suicide is terrifying to the survivors, a “world of dark earth,” in a way. To enter that realm, to face it, she examines the surviving family members’ responses to suicide. Their responses take one of two paths, silence or narrative. While poring over her father’s papers, Patterson finds notes James made attributing his dad’s death not to suicide, but to murder. James had attempted to impose a narrative of shady characters and criminal enterprise onto his father’s death in order, Patterson claims, to reject the suicide. He was eight when his dad shot himself, and even in his older age, James was unwilling to accept his dad’s death as a suicide. Why, Patterson wonders, was her father so resistant to his dad’s suicide when evidence pointed to that manner of death?

So why did my father believe in his theory of murder, however untenable some of its conjectures might have been? The violence and disruption of his [James’s] past, maybe, growing up in the shadows of Prohibition, the Great Depression, and the historically violent and chaotic culture of Crawford County. But more, I think, because believing [his dad] Edward was murdered would have made it easier to avoid the questions a loss by suicide might present. Under what circumstances, if any, does suicide make sense? Under what circumstances, if any, is it an appropriate thing to do? Is life itself worth having? Is the fact that you’re alive a good thing?

He wasn’t the only one who avoided the subject. After Edward’s death, my grandmother Leah did everything she could to put him behind her. In the weeks following the funeral, as she sorted through business affairs and began coping with the reality of supporting a family, she stopped talking about her husband. What happens, I wondered, to a child whose father literally and figuratively disappears?

James faced that “world of dark earth” by building a narrative which restored his father to a loving man and public servant (he’d formerly been a U.S. congressman), a man who wouldn’t abandon his family. The question underlying Patterson’s memoir is not why do some people kill themselves; rather, it is how do the survivors make sense of their death? If it’s true they wanted it, then how do we create a mental structure around it to withstand the chaos, the shame, the abandonment that a suicide generates? The answer frequently is that we don’t apply words to it or we don’t talk about it. We shut our mouths in a tacit agreement with the deceased; we will collaborate in their disappearance. Or like James, we’ll make up a fiction and thereby deny the suicide. Both responses are harmful because they avoid the truth. Better to face it and name it, Patterson seems to say, than to let the truth—even if it can never be fully known—sink into some dark void.

Milkweed

$25.00 Hardcover | Buy Now

David MacWilliams earned his MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Ashland University, Ohio in 2011. His creative nonfiction and fiction have appeared in Pilgrimage, Mason’s Road, Apple Valley Review, Creative Nonfiction, the tiny journal and elsewhere. He blogs at https://wordpress.com/home/oldageandgravity.blog. He lives in Cloudcroft, New Mexico with his wife.

Carole Mertz is the author of the poetry collections Toward a Peeping Sunrise and Color and Line. She also reviews books for U.S., Canadian, and Indian literary journals, among them Arc, Bangalore Review, Taj Mahal Review, and World Literature Today. A semi-retired musician, Carole resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio.

Carole Mertz is the author of the poetry collections Toward a Peeping Sunrise and Color and Line. She also reviews books for U.S., Canadian, and Indian literary journals, among them Arc, Bangalore Review, Taj Mahal Review, and World Literature Today. A semi-retired musician, Carole resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio.