By Marsha Lynn Smith

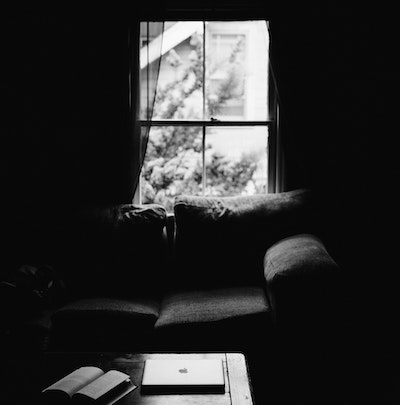

My toddler grandchild sits still on the carpet between my knees, her back cushioned against the sofa. I consider detangling her springy hair coils. Should I fix her hair similar to the way my mother did mine? Most school mornings, she would twist my bristly hair into a short, thick braid. On special occasions, she hot-combed it smooth into side-by-side puffs with sausage bangs.

In time, I styled my hair in ways that appealed more to me and less to African-American middle class standards. It has been flat-ironed or fingered into a curly Afro. Crocheted with blonde extensions. Wet-set on spongey rods. Gold thread laced within cornrows. Colorful beads attached to the tips of a hundred dangly micro-braids. Before vacationing in Europe and Africa, a skilled braider gave me several long, thick plaits separated by zigzagging angles. I could enjoy my excursions, undistracted if humidity or some other element affected my hair. What a luxury.

The moment will come when my granddaughter appreciates hair as an expressive part of her identity. A physical connection to her African roots. A reminder to the world of her place of origin, regardless of how she chooses to wear it.

From my couch position, I look down at the tips of her corkscrew curls. They stand up like points on a princess’s crown. Best to leave her hair in this naturally royal state. I smile when a spray of coconut oil rests upon it, like pixie dust.

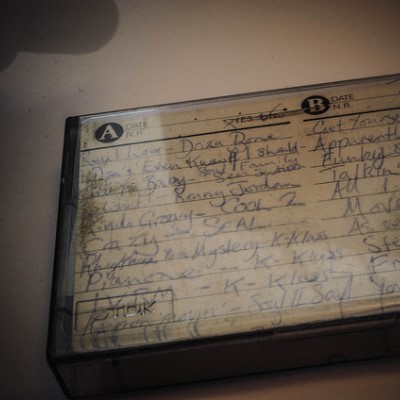

A transplant from Chicago to southern California, Marsha Lynn Smith relishes how time seems to stand still while writing. The Los Angeles Review of Books and Femme Literati: Mixtape are among the outlets publishing her work. She likes to read historical fiction novels, and admits to binge-watching international TV dramas.

Photo by Amy-Leigh Barnard courtesy of Unsplash

0 Comments