By Robert Barham

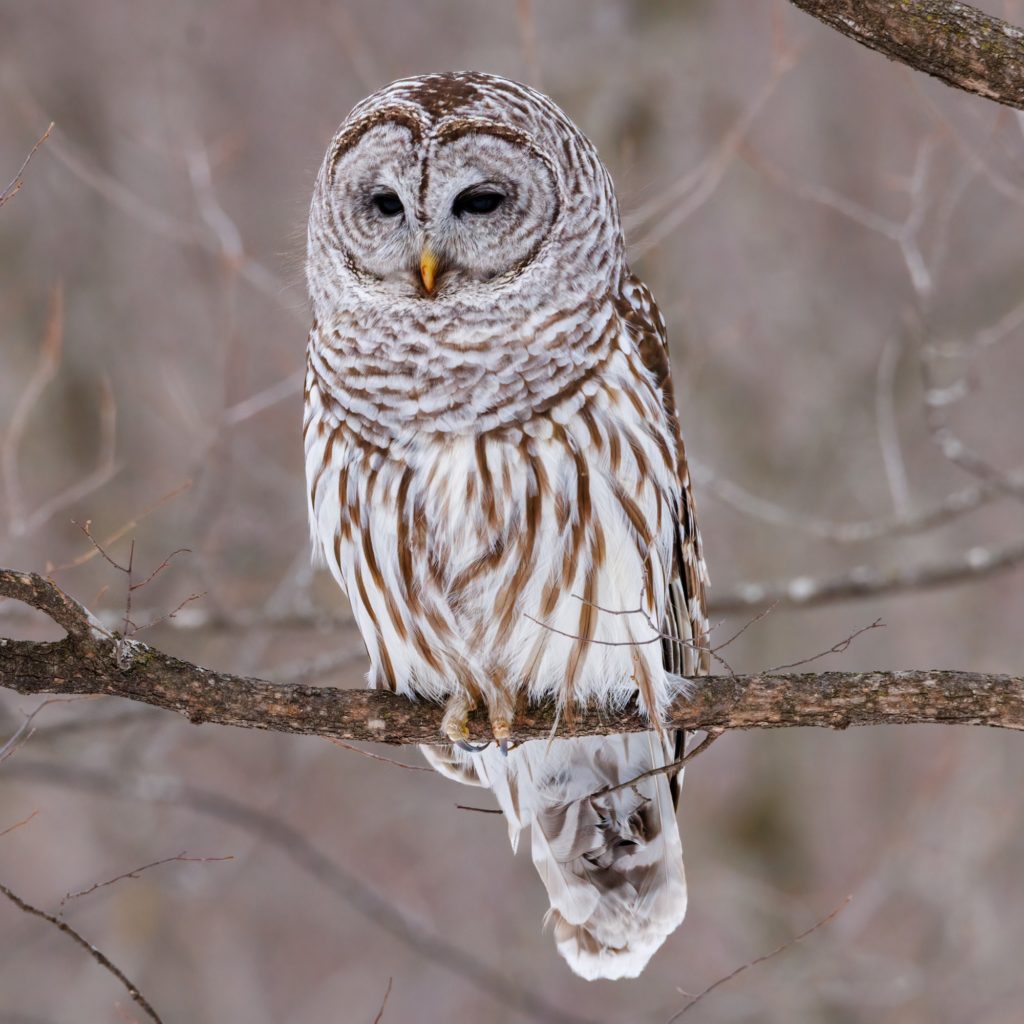

Hunting was a source of food, the main recreation, and a rite of passage. Everyone hunted. Still, I had a choice. It was dusk, and my father and I sat beside a crop field, plowed over in the fall. We watched from woods that earlier were full of birdsong, canopied by oak, cottonwood, and pecan, when two deer appeared—a doe and its fawn. “The fawn is old enough to wean,” my father whispered. Then he asked if I wanted to shoot. What I wanted was to be like him, a hunter, and I don’t remember even hesitating. Afterwards, we carried the doe to our barn where we saved the meat, slipping viscera from its body, the air thick with the smell of blood. What I remember most, decades later: a feeling of grief after I pulled the trigger. The fawn stayed close to its mother’s body, watching us. “It’s just confused,” my dad said, and a doorway opened between before and after, uniting a word and its meaning, death and the thing itself. I wanted to have my act undone, to get back to the moment those deer stepped into a pool of green grass that held the daylight. Recalling this memory now, I imagine the fawn at the edge of dark woods, and I’m an image in its black, glassy eyes—a vision of fading light in a world suddenly altered, made strange by predation, the change irrevocable as a gunshot.

Image by Olga Shenderova courtesy of Pexels

0 Comments