By Erin Slaughter

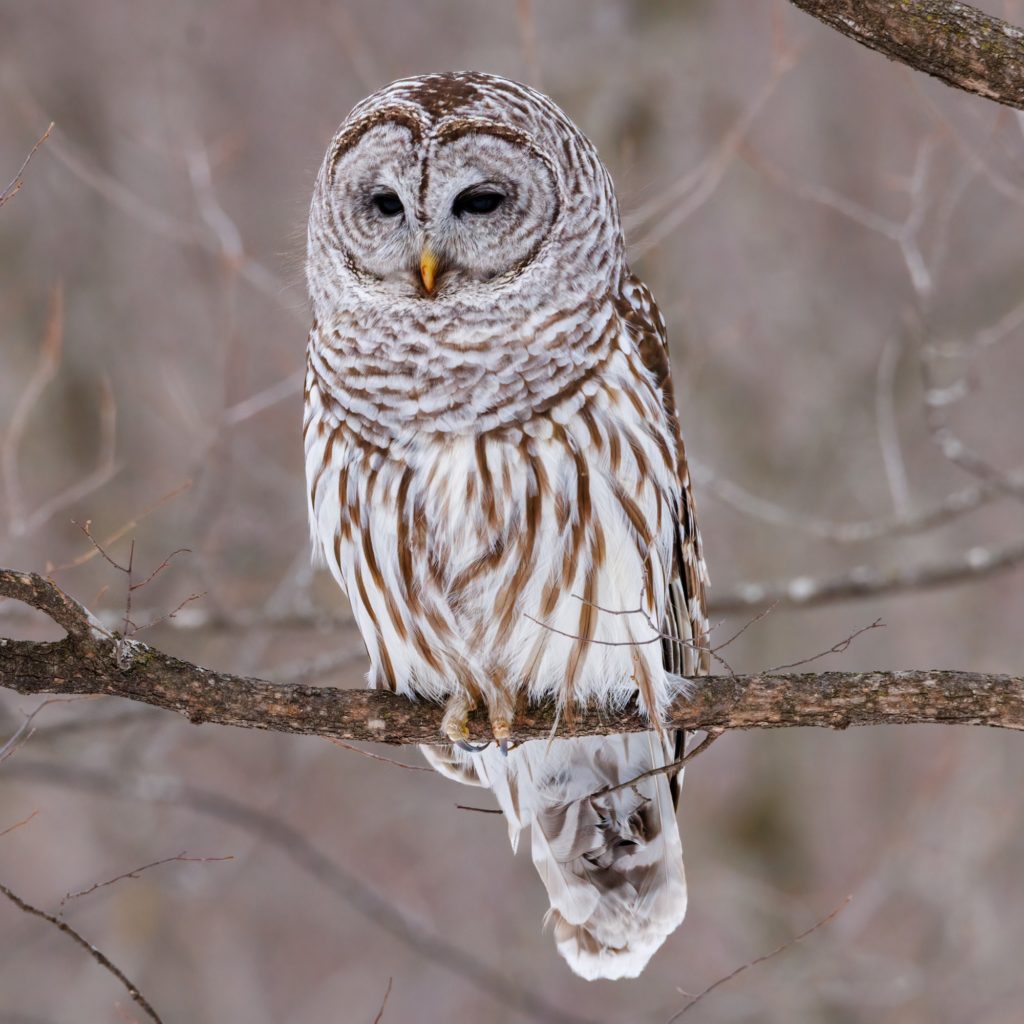

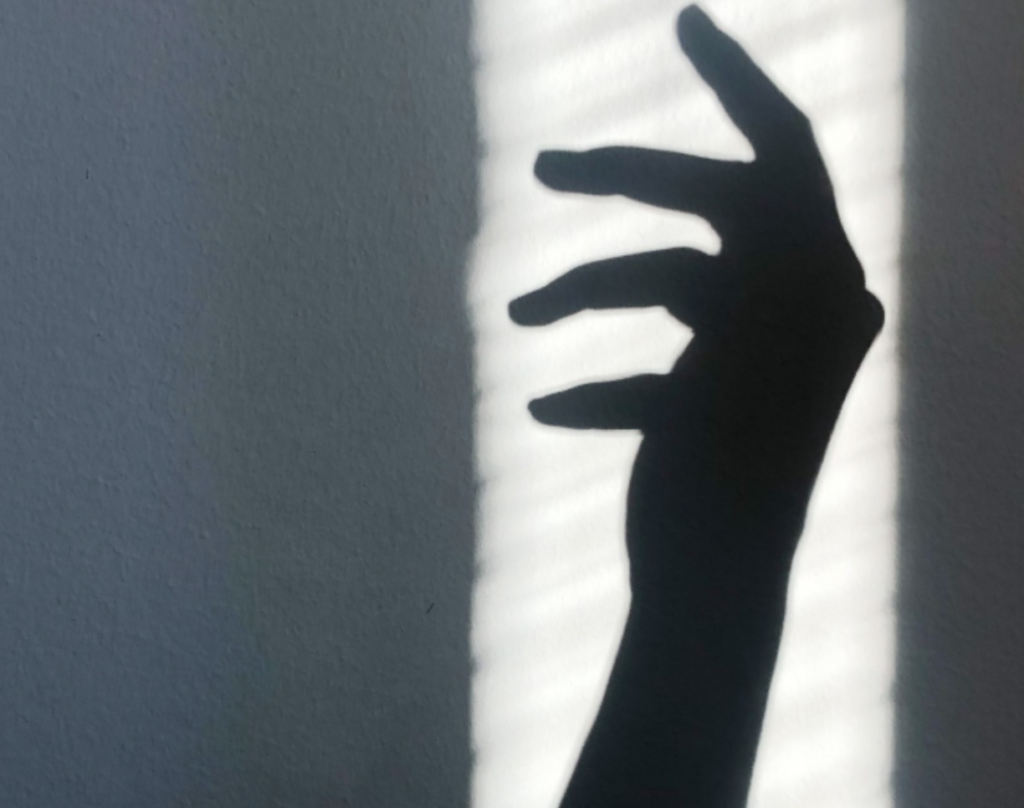

It is always almost raining. That’s something they never tell you about Seattle; they talk about the rain, but not the days the air holds its breath. Over the phone, Grandma asks if I can see Mount Baker from my window. To me, the mountains are still intimidating and holy. I haven’t yet learned to live among them as domestic creatures, the way we forget that house-cats are made of lions.

Grandma tells a story: “When we visited Tacoma, Steve was a toddler. We saw Mount Baker off in the distance, and he said, ‘Ma, why’s it floating?’ I explained there was a cloud in the way. He didn’t believe me.”

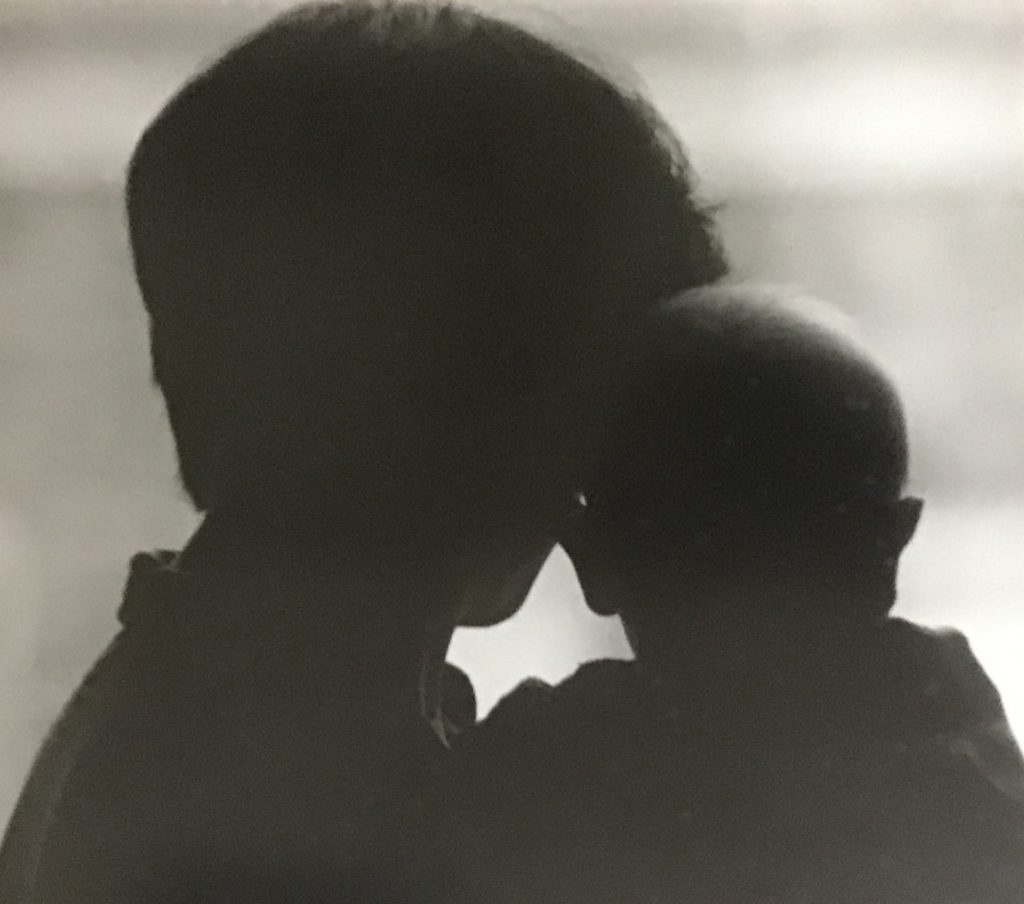

It has been long enough that when she says, “Steve,” I don’t immediately think, “my father who is dead now,” but I can imagine the little boy, blonde and pantalooned, and his conviction in the truth of floating mountains.

I can laugh, and do. I’ve long since domesticated grief and whatever grief turns into. Grief the cat, rarely resembling grief the lion.

There’s only so much to say about grief before it becomes something separate, something that lives on its own in the world and has little to do with you. Even the word grief sounds tedious, like trying to make conversation while walking uphill. There is only so much distance available to us–behind, between, before. And after us.

Above the streets of Beacon Hill, the sky exhales. I gulp down frozen air and hold my breath.

Erin Slaughter’s poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction has been published in The Harpoon Review, The North Texas Review, Off the Coast, GRAVEL, and 101 Words, among others.

Image provided By Dllu – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42654838y via Wikipedia’s Creative Commons licence.

0 Comments