By Aaron Newman

Aunt Beverly was not my aunt at all. She was the family hairdresser and a friend of my mother’s. She believed in God, but her allegiance was firstly to those around her. She was good at understanding, like when her younger son started smoking weed, or when her older son’s girlfriend stayed the night, or when her husband became a penis pump telemarketer. She was a wacky woman of the world; and when she cut our hair, I heard my mother laugh at and sympathize with things I never could’ve imagined possible.

When I was twelve or so, I shared a poem with Aunt B that I was to read at the public library later that evening. It was called “Summer Skies and Her Silver Eyes,” but she read it as “Summer Skis.” When I corrected her, she laughed first, then continued, line by line, with enough care to make me blush.

She read us a poem of hers too, about an old crush, a painter with a ponytail. It was called “Did You Notice Me?” The poem details her weekly changes—new nail polish and hairdos, perfumes and dresses; and that bright red lipstick that made her glassy green eyes sparkle and her clustered freckles pop. Did you notice me? she asks at the end of every line.

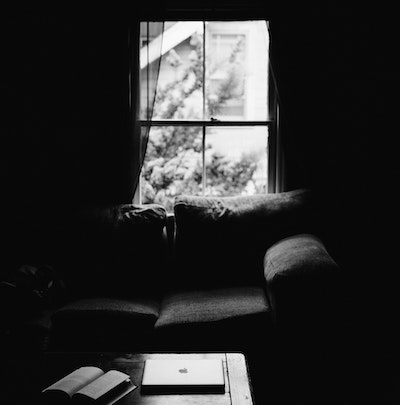

My mom sat across the room, slouching back under the hair dryer, grinning, with a hand on her head. She was paying attention, to Aunt B, to me—to poetry.

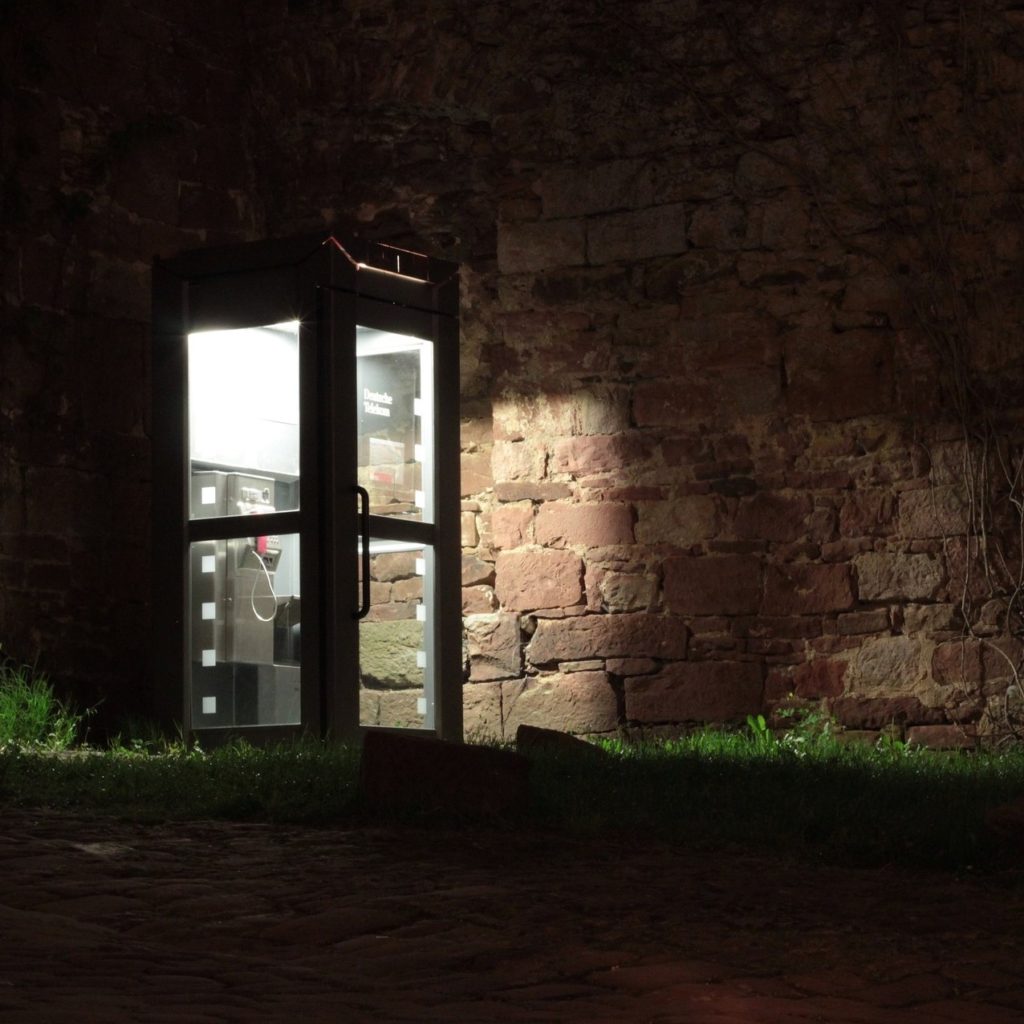

Image courtesy of Pxhere

0 Comments