By Andrea Caswell

Originally posted November 17, 2014.

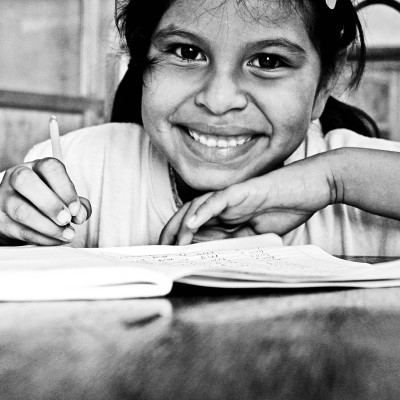

As a child, when adults asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I had plenty of answers, but they all sounded like Halloween costumes. Race-car driver. Astronaut. Olympic track star.

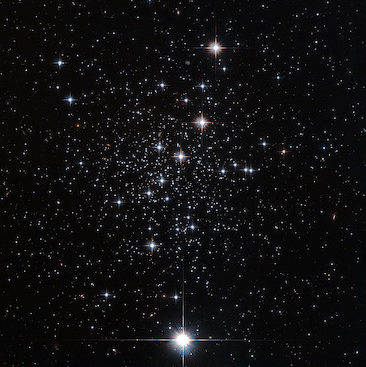

My father was a rocket scientist for NASA, so the idea that a person could be anything, in this world or beyond, was real to me. With his telescope we peered through the reaches of time, to stars and planets light years away. Some Saturdays, we drove an old sports car to the building where he worked. Guarded gates parted when my father flashed a badge with his picture on it. These were the gates to the final frontier.

In a warehouse as big as a soundstage we stepped quietly through the weekend hush of unlit offices and classified information. My dad pointed out where the mathematicians worked on equations.

“Some problems take years to solve,” he said.

“Do you mean just one problem, Daddy?”

“Yes,” he said, drawing the word out slowly, because it was so hard to fathom. “A single problem.”

My father would never lie to me, so I knew this must be true, but it was an enormous idea for a little girl. In the twinkle-star world of a child, it made me believe that any problem could be solved. Any dream could become a reality. This was not magical thinking on my part; the proof lay all around me. My father had a piece of the moon on his dresser.

Photo “Star Trails Over NASA” provided by Zach Dischner, via Flickr creative commons license.

0 Comments