By Darien Andreu

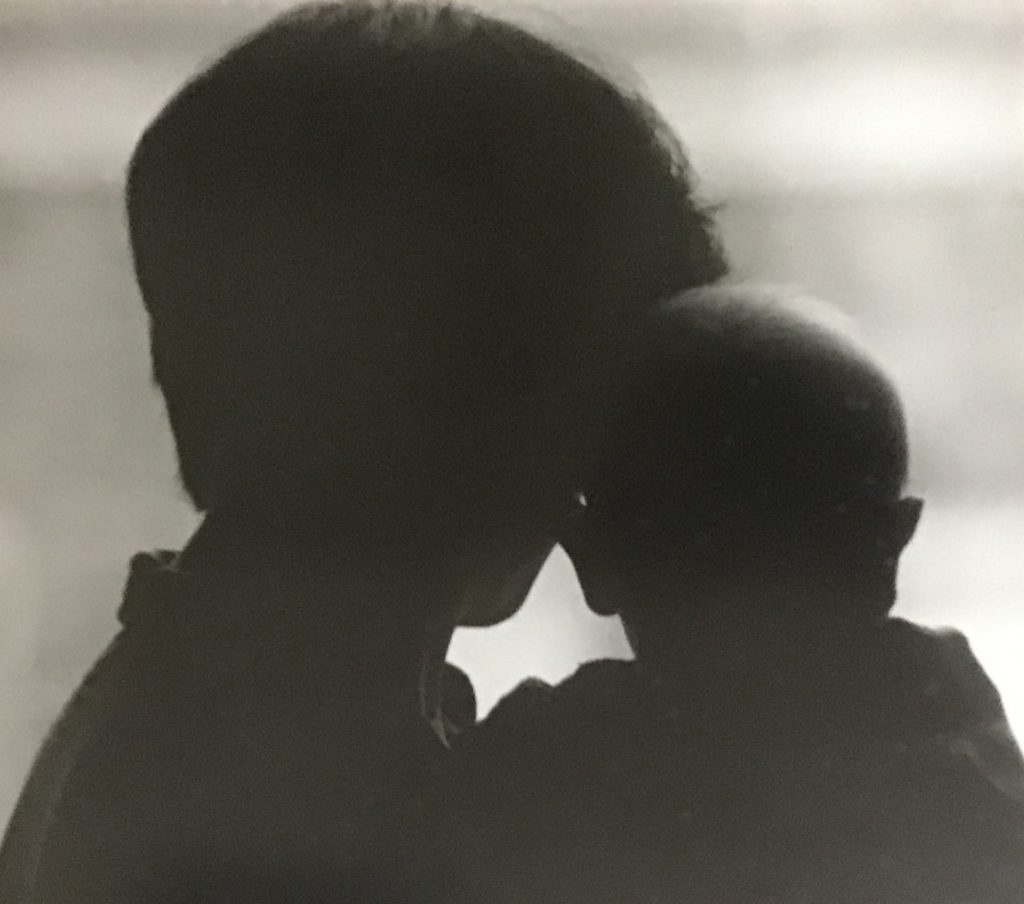

My husband raps on the kitchen window from the deck outside where the cat sews in and around his legs. “Can you hand me that thing?” he says, pointing unsteadily. The scar from his brain surgery curves over his left ear. An upside-down horseshoe.

I glance about the kitchen…for a thing. Nearly six weeks of radiation to the left side of his head has shrunk his brain tumor by a third, but it has also loosed the moorings of his words.

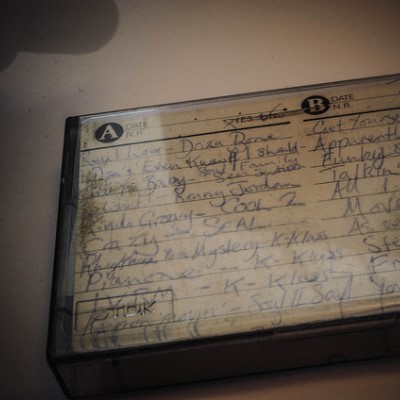

Now “thing” might mean another can of cat food. Last night, the “thing” was his box of pills. On campus “thing” had meant his notes for Existentialism. In another semester, this inspecificity will lead him to resign, but right now, I, a teacher of English, am mesmerized.

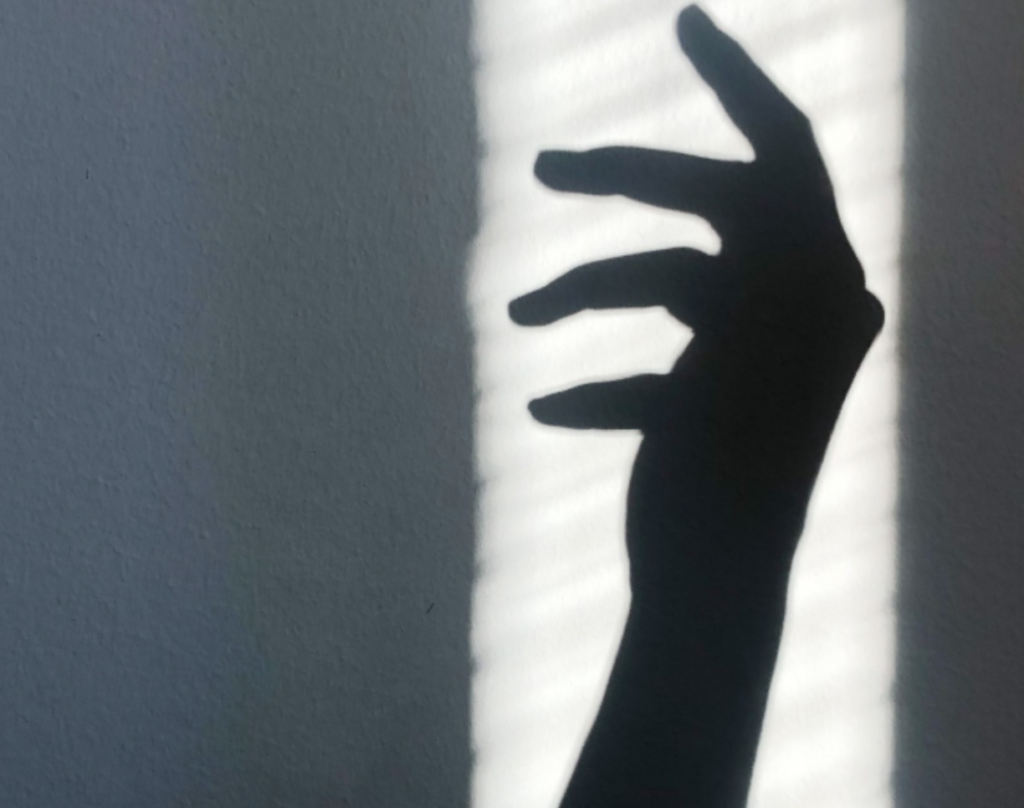

His linguistic instability has let me see the capriciousness of words: “no” can really mean “yes,” “shirt” can actually mean “pants,” “Plato” can mean “Socrates.” No meaning seems stable; intention is really all that’s left—or right. And isn’t that enough? If I weren’t so literal. If I could listen past what he says, beyond the utterances I hear, to the heartbeat of what is really meant.

He raps again on the window as the cat begins to howl. “THAT thing,” he says, pointing to the dishtowel in my hand, and the spoon that has been there all along.

Darien Andreu teaches in the English Department at Flagler College in St. Augustine, Florida. She also serves as President of the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Society.

Image courtesy of Adobe Stock

0 Comments