By Gail Folkins

September 7, 2015

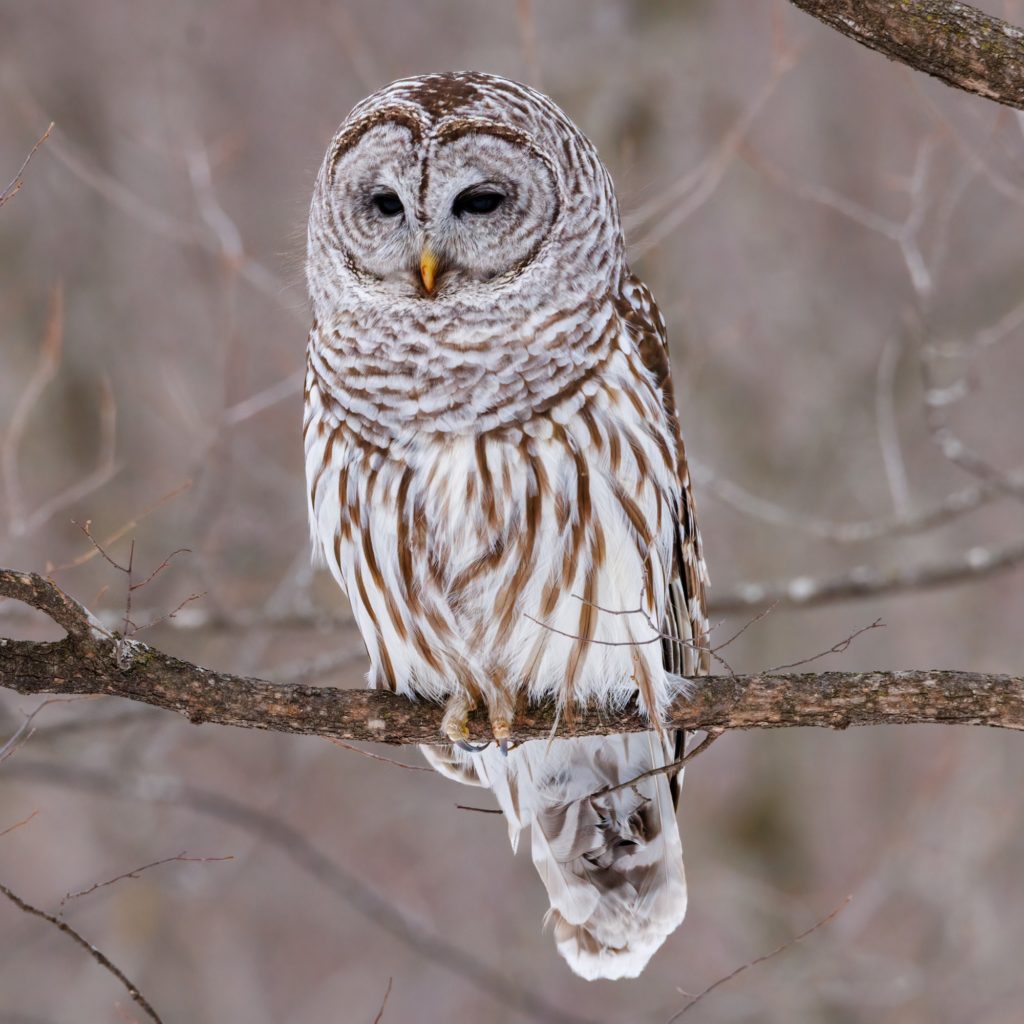

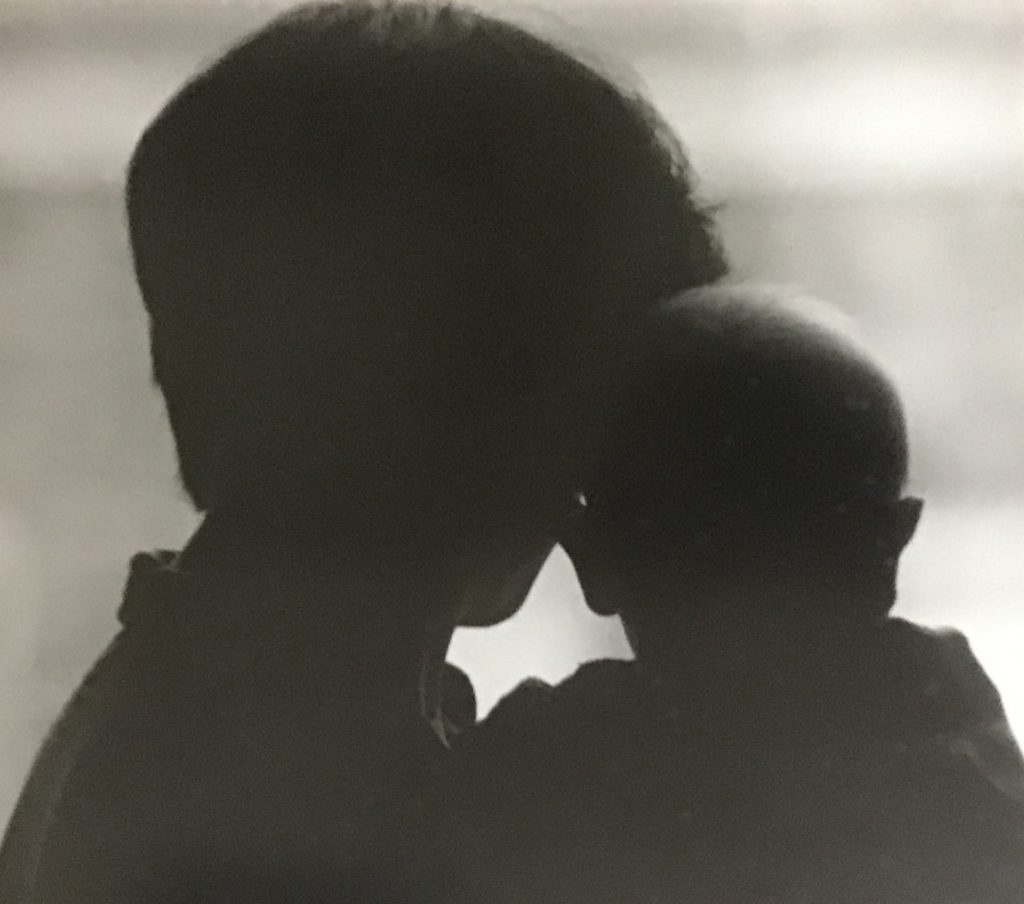

On a dirt road behind a Midwest farmhouse, John and I walk between last year’s corn stalks and the soybeans to come. Although spring appeared in the form of a printed milestone on the calendar, the wind clips and scatters spoken words. Overhead, a pair of just-returned Canada geese honk and carry on, their long necks stretched toward a pond in the middle of the field. Their bodies turn bronze in dusk, but it’s the blending of their voices that makes us curve our necks upward. The pair’s separate tones are distinct yet sound close enough to call harmony. It’s a major third interval, says John, a musician, and I stop to listen, wondering about the cadence of our voices, sometimes in sync and other times varying, a necessary dissonance. Following the field’s just-plowed furrows, the two birds fly a half-step apart. John and I won’t stay long in this place, restless and wandering on our own cross-country journeys, the resonance we share more important than the route. Its grip softer now, the wind quiets enough to make out bits of conversation. The geese finish each other’s sentences all the way to their roost. We turn for home, ears straining toward the recognizable warmth of this well-rehearsed score, an imperfect duet of well-matched notes.

Gail Folkins often writes about her roots in the American West. Her nonfiction book Texas Dance Halls: A Two-Step Circuit was a popular culture finalist in Foreword Reviews’ 2007 Book of the Year awards. Her nature-themed memoir, Light in the Trees, is forthcoming from Texas Tech University Press.

Photo “Rising” provided by Don McCullough, via Flickr.com creative commons license.

0 Comments