By Deb Werrlein

Dad bought a Miami of Ohio ashtray in 1957—a tin dish with a beanbag for a base, a red M on its side. I imagine him, eighteen in his dorm, tamping out butts and laughing through smoke over cards as he perfected his bridge game and became his own man.

Later, when I was less than waist high, we’d walk to the beach, his tanned, strong hand enfolding mine while the other carried the M-emblazoned tray with a Winston dangling, the smell of tobacco like home—the world no bigger than us. As I grew, the M sat on the dinner table, the card table, the piano. Then the end table by his favorite recliner. Eventually, Mom put hands on hips and relegated the vessel to out-of-doors. It sat next to the barbecue and corn for shucking as the first and then last of eight grandchildren came for dinners until Mom said, “get rid of that old thing,” and it disappeared—though the habit remained. By the time great grandchildren arrived, we’d long forgotten about it.

Now, I’ve found it in the shed. Its red M cracked and faded, its concave tray charred to disfigurement, like the blackened inner curve of an atrophied lung. He’d kept it—even after he quit on the day he learned of the cancer. Seeing it overwhelms me, like accidentally swallowing an ice cube, but I don’t feel anger as I’d expect. It doesn’t remind me that he smoked. Only that he lived.

Deb Werrlein is a freelance writer and editor working in Fairfax, VA. In addition to Beautiful Things, her flash essays have appeared in Brevity, The Sun, The Los Angeles Review, and others. Werrlein’s longer work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in a variety of journals, including Creative Nonfiction, LitHub, and Mount Hope.

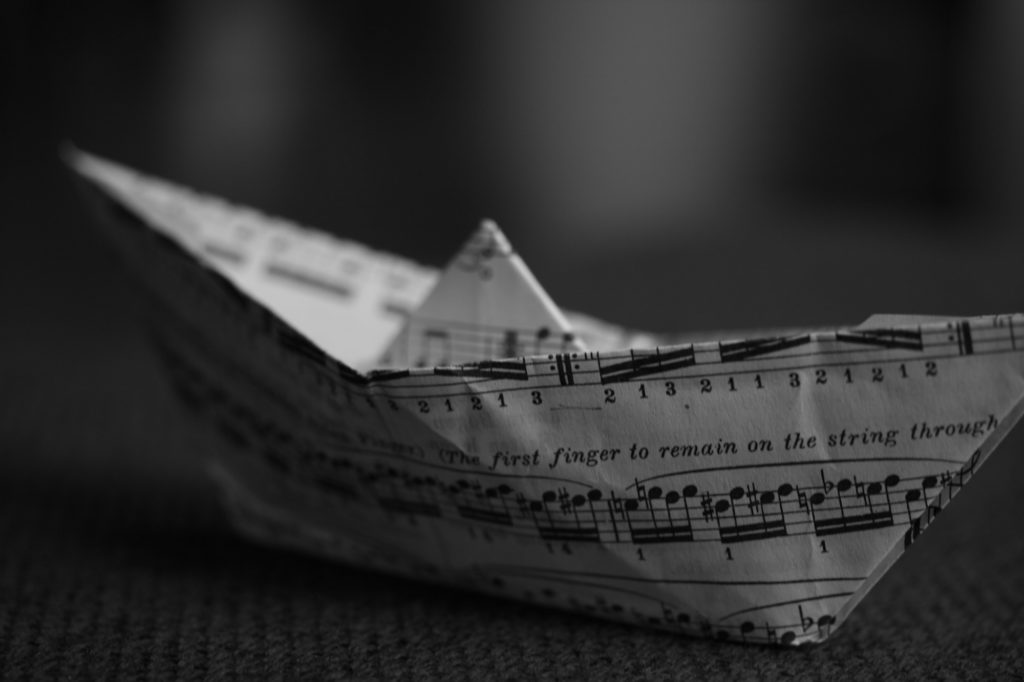

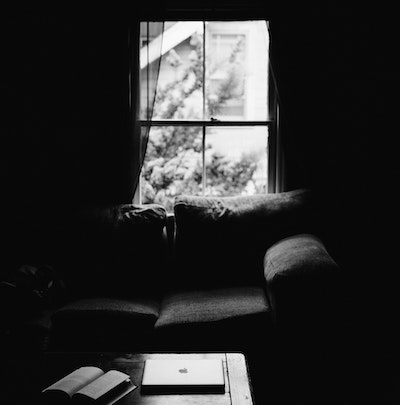

Image by Dmitry_Tishchenko courtesy of iStock

This is incredible.

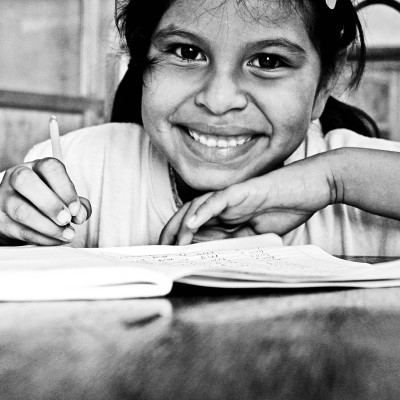

You described my late husband so perfectly. He, too started at MIT in 1957, perfected his Bridge and billiards games. Although he gave up the smokes in 1987, the cancer got him too soon. We had 50+ glorious years together, raised 4 kids, and he lived to see our beautiful grandchildren. Yes, they LIVED. Thank you for writing this.

Beautiful!

Beautiful, thank you!

“Like the blackened inner curve of an atrophied lung” and “accidentally swallowing an ice cube”–powerful and surprisingly beautiful. I loved following the ashtray as it changed over time and revealed the narrator’s love for her dad, all the way to the end.

The swallowing an ice cube reference got me. What a beautiful piece.

“The smell of tobacco like home — the world no bigger than us”. So beautiful!

Talent exuded in the images that bring memories–even as we don’t wish them, we cherish them.

Thanks.

— i’m so glad there’s a place to say how much i loved this piece. loved the ice cube image someone mentioned above, loved the line about the reminder that he lived. it was very economical in words, but deep in emotional impact. nice work.

— i’m so glad there’s a place to say how much i loved this piece. loved the ice cube image someone mentioned above, loved the line about the reminder that he lived. it was very economical in words, but deep in emotional impact. nice work.

Love it. I already shared it with my writing group as a wonderful example of using objects as conduits to stories.

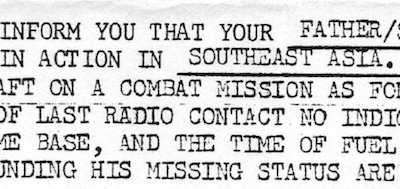

Beautiful. Reminds me of my dad, who learned to smoke while in the arm during WWII. Who died of lung cancer in his 70s. I have a few of his molded glass ash trays. He lived. Thank you so much for this story.

I could smell my Dad’s cigars as I read this. He was stationed in the Panama Canal Zone during WW II where, I suspect, he learned to smoke some very good cigars. One of his old cigar boxes, no longer perfumed with tobacco, sits in one of my cupboards holding items I don’t use very often. Thanks for this lovely memory.

great last line” It doesn’t remind me that he smoked. Only that he lived.”