By Renata Golden

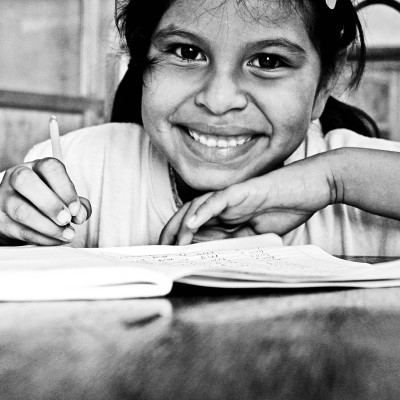

My mother taught me to look at birds by pointing out their details, like bill shape and breast color. She taught me the names for American Robin and House Sparrow—city birds, the kind we could see in our Chicago backyard. She named Northern Cardinals and Red-winged Blackbirds—picnic birds from forest preserves and holiday weekends in late summer.

To name something means knowing where it belongs. Blue Jays mean country—the Indiana shore along the southern tip of Lake Michigan, where I raced my sisters up the dunes to the beach. From the shadows, Blue Jays shrieked, squawked, and laughed; they cawed like crows and screamed like hawks. These are the sounds of my childhood summers. One blast from a jay and I am instantly in a copse of Indiana elms with sand in my Keds.

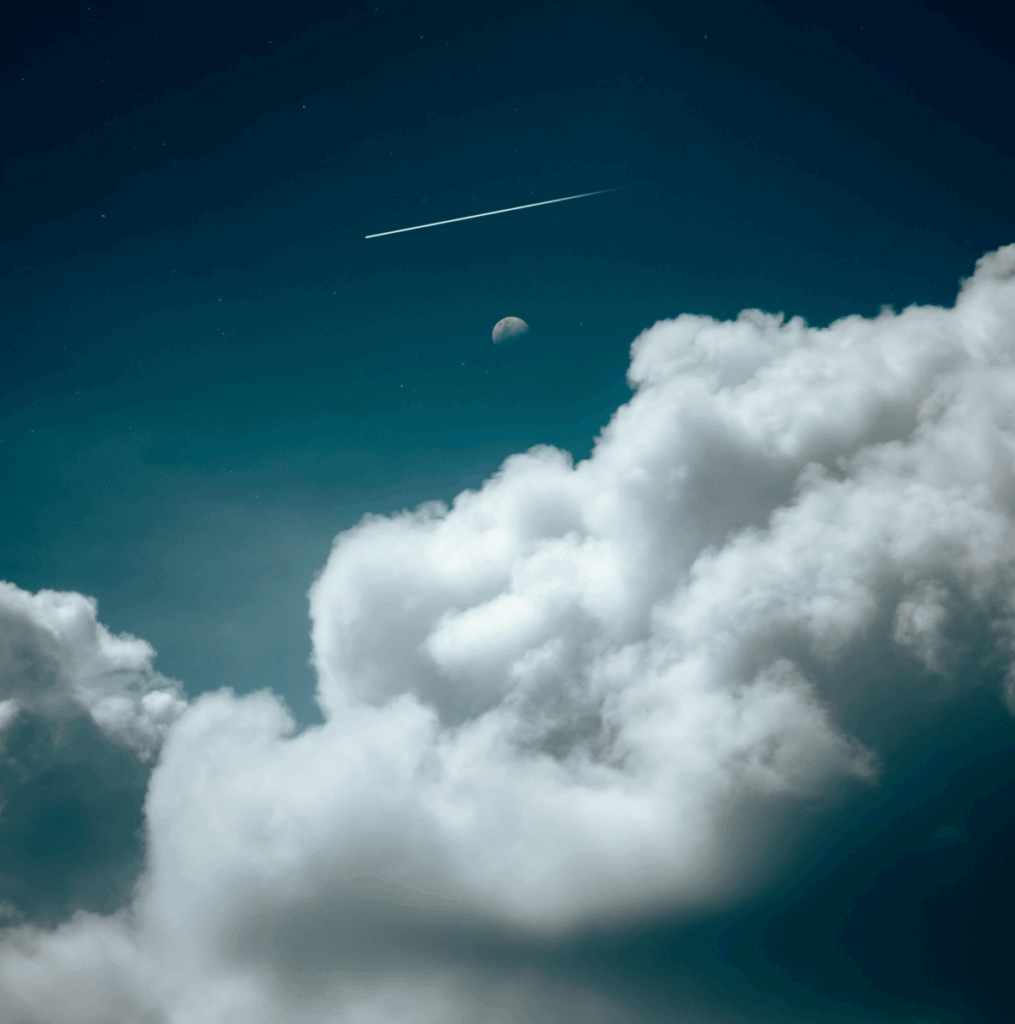

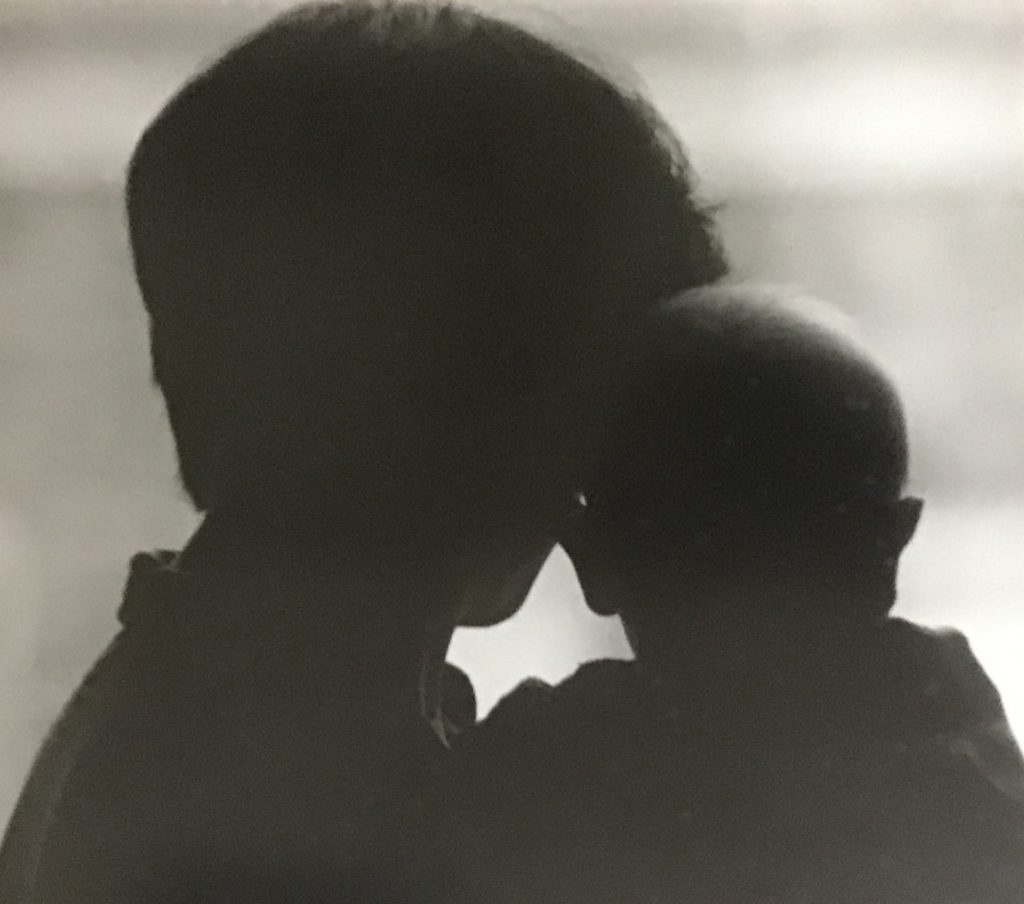

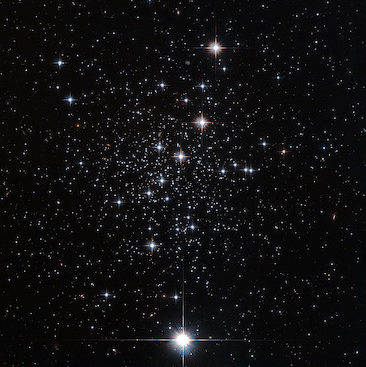

Birds are born knowing that someday they will leave everything familiar and travel, sometimes thousands of miles, to a place they have never been, to eat foods they have never tasted. From my home in the New Mexico mountains, I watch birds like Greater Roadrunners and Scaled Quail and learn their sizes and shapes. If my mother were still alive, I would show her a Western Tanager and teach her the taxonomy of flycatcher families. I would take her birding in all the other places I have lived, where she could learn shorebirds and eagles and desert wrens. She would call me by the name she gave me, and I would know where I belong.

Renata Golden lives near several Important Bird Areas (IBAs) and has long participated in multiple Christmas Bird Counts each year. Because counting birds gets easier as bird population numbers dwindle, a result of climate change and habitat loss, every bird becomes even more important.

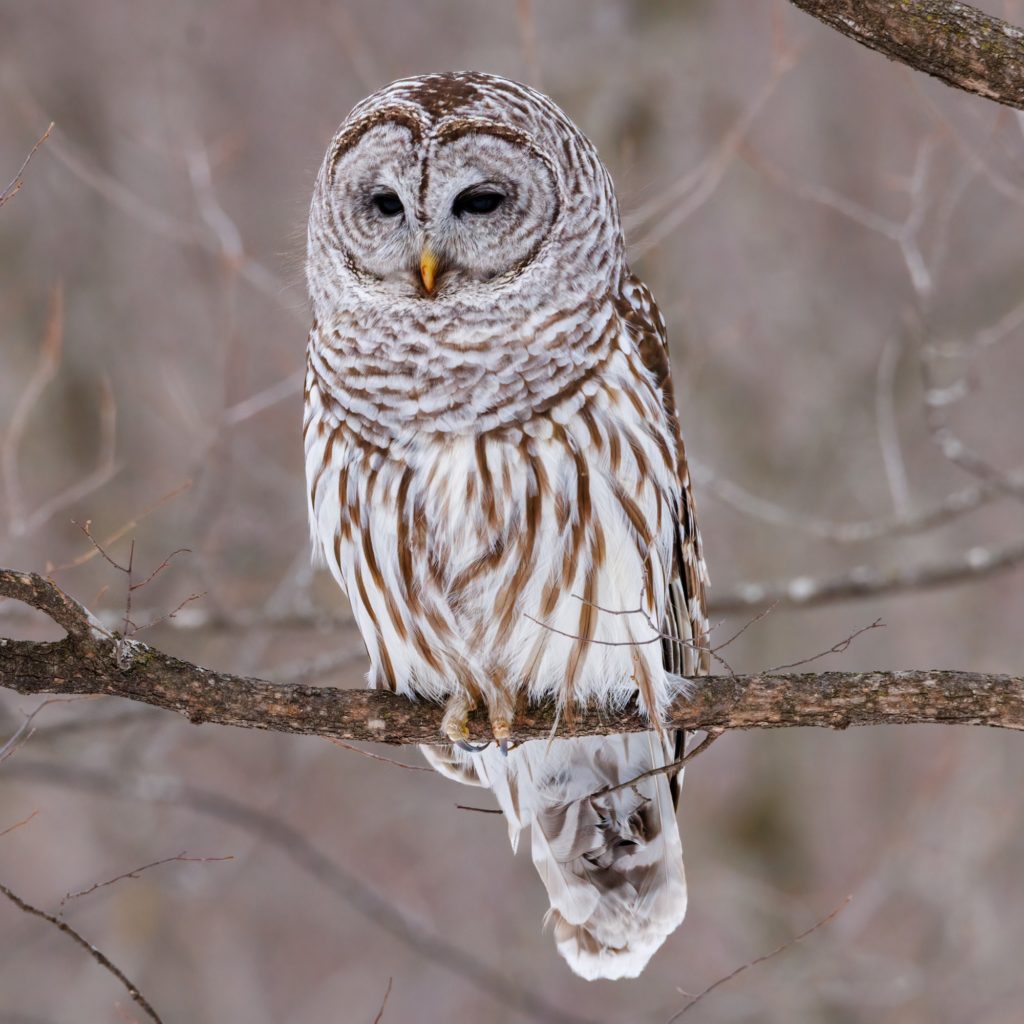

Image by Pixabay courtesy of Pexels

Memory takes flight and connections are made in this lovely and evocative essay.