By Cheryl Lynn Smart

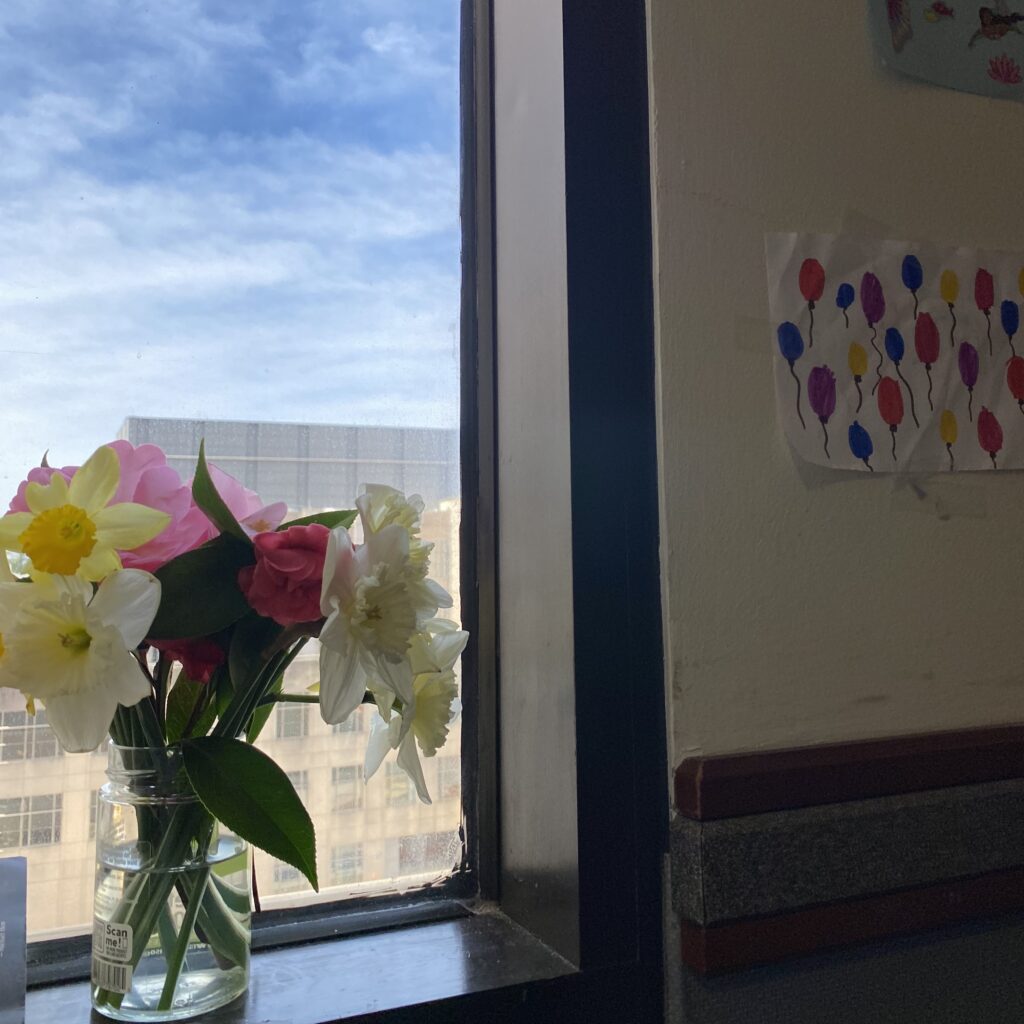

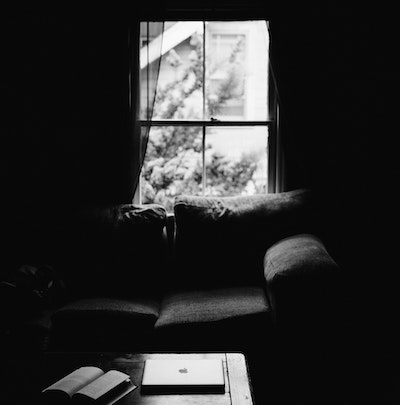

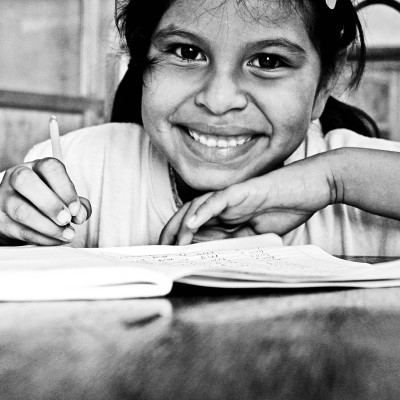

Tim’s apartment was cleaned and all his belongings put out on a curb in the parking lot. This is the saddest part. Seeing a life in a parking lot. My son took Tim’s desk and brought me a table. This seemed both right and wrong at the same time. I moved the table to a place of prominence. No one can come into my home without seeing it, without paying homage to Tim.

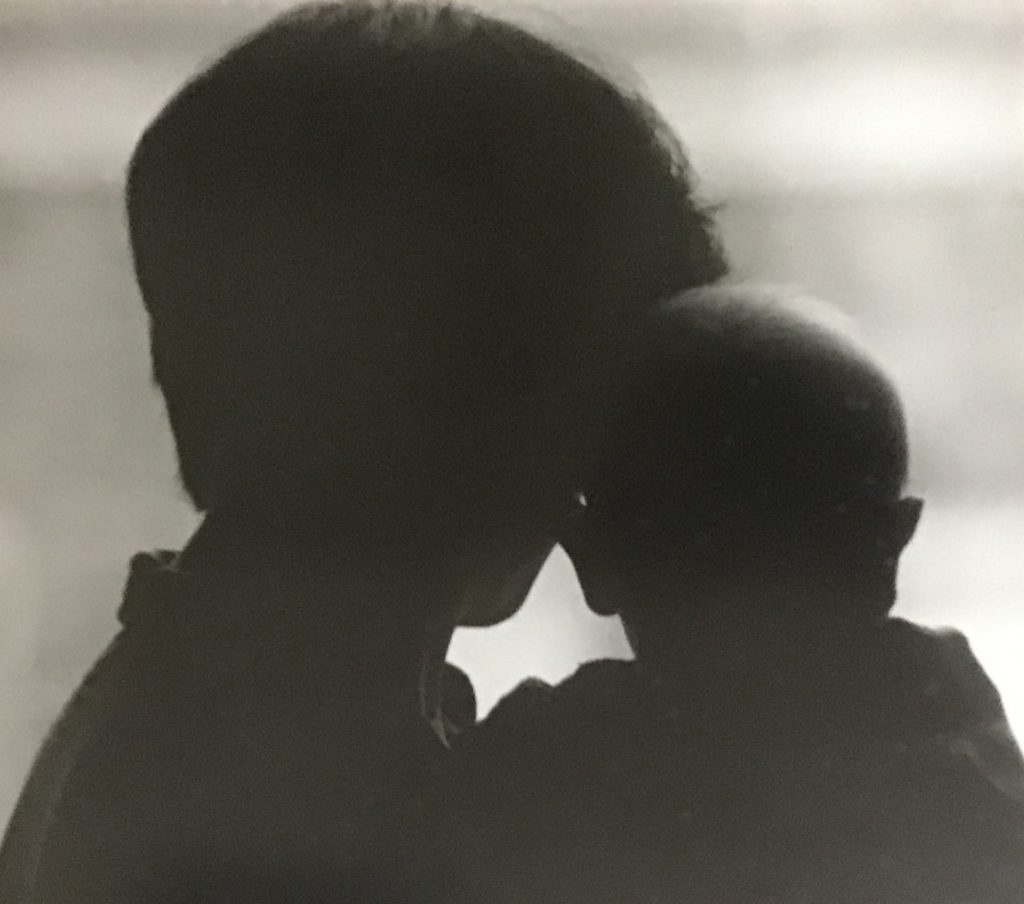

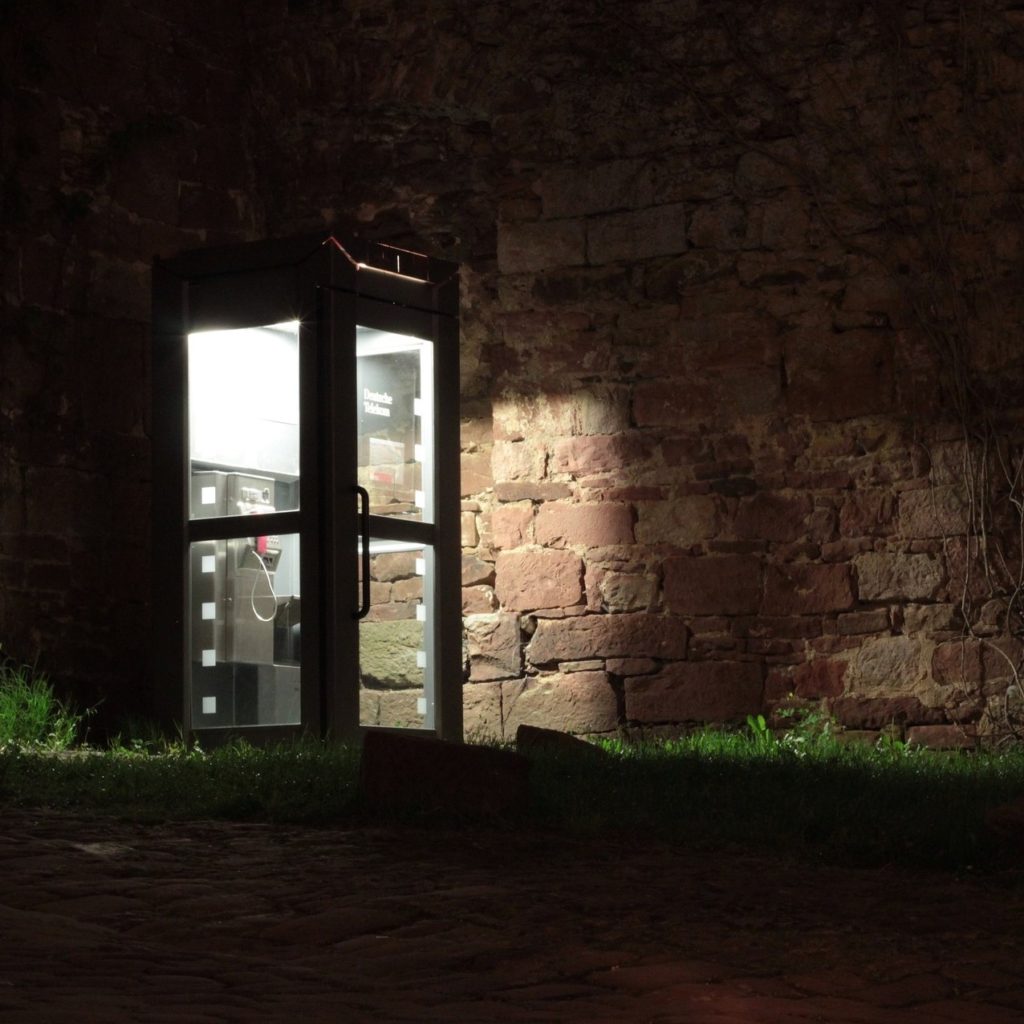

Tim lived in the apartment above my son and his wife and their young daughter for several months. One day, the police came asking questions. Tim is dead. Had been dead for days when the police showed up. Found dead in his apartment, alone. Tim kept to himself, was notably quiet, was no trouble, was no one. Invisible, my daughter-in-law says. It’s just the way he was, she says.

My son calls Tim ‘Dead Man Tim’ or ‘Dead Tim’ not with disrespect or to be facetious but in the way one would laugh at a funeral, with Albert Camus absurdity. We don’t have a place in our psyche for this. We don’t have a folder to put an unknown person whose existence is only marked by belongings dumped in a parking lot.

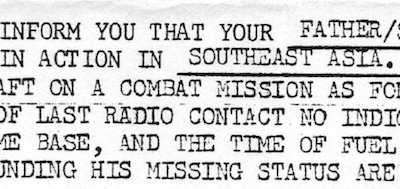

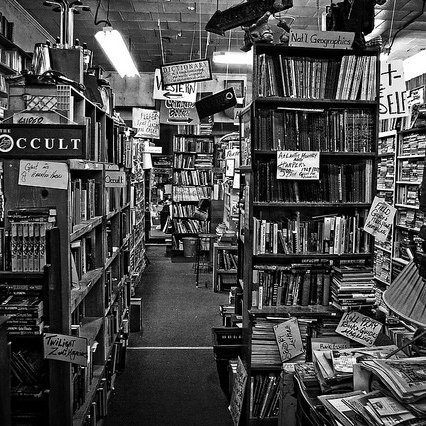

Pieces of crinkled paper inside Tim’s desk show things needed at the grocery, how much money is left this week and who isn’t getting paid if there isn’t enough. To-do’s and don’t forgets. Don’t forget. Lungs, stop breathing. Don’t forget. Heart, stop bleeding. Don’t forget. Body, still. Body, don’t forget.

Carved spindles, curved lines, painted vines shroud olive-stained wood. Top left drawer pull has loosened, don’t forget. The finish is worn thin on one corner of Tim’s table.

Cheryl Smart is an essayist and her work can be found in Gulf Coast, The Collagist, GrubStreet, storySouth, Shooter Literary Magazine, Cleaver Magazine, Word Riot, Southern Writers Magazine, and others.

0 Comments