By Ona Gritz

December 30, 2019

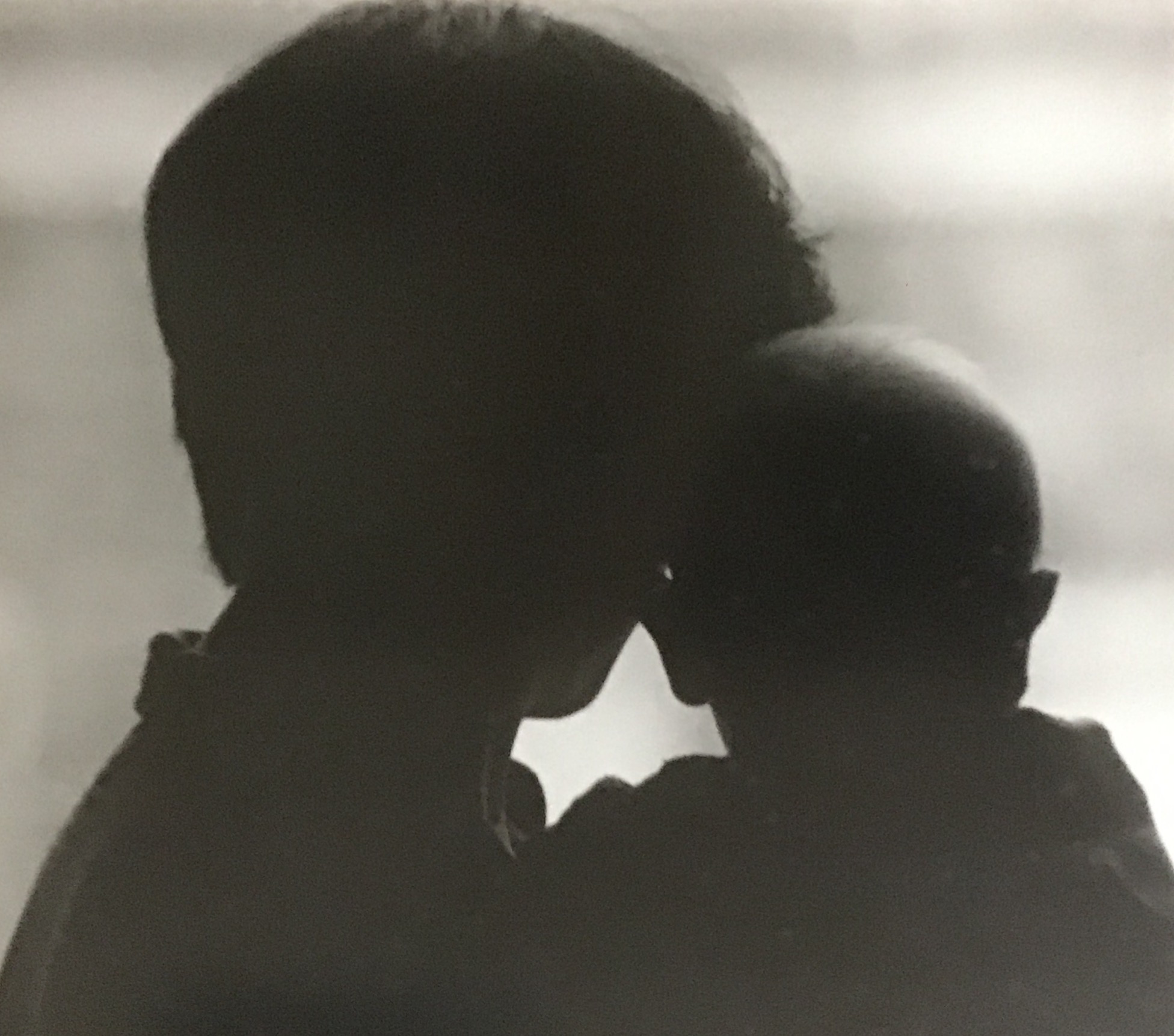

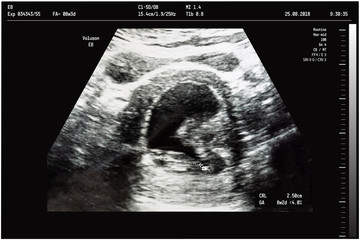

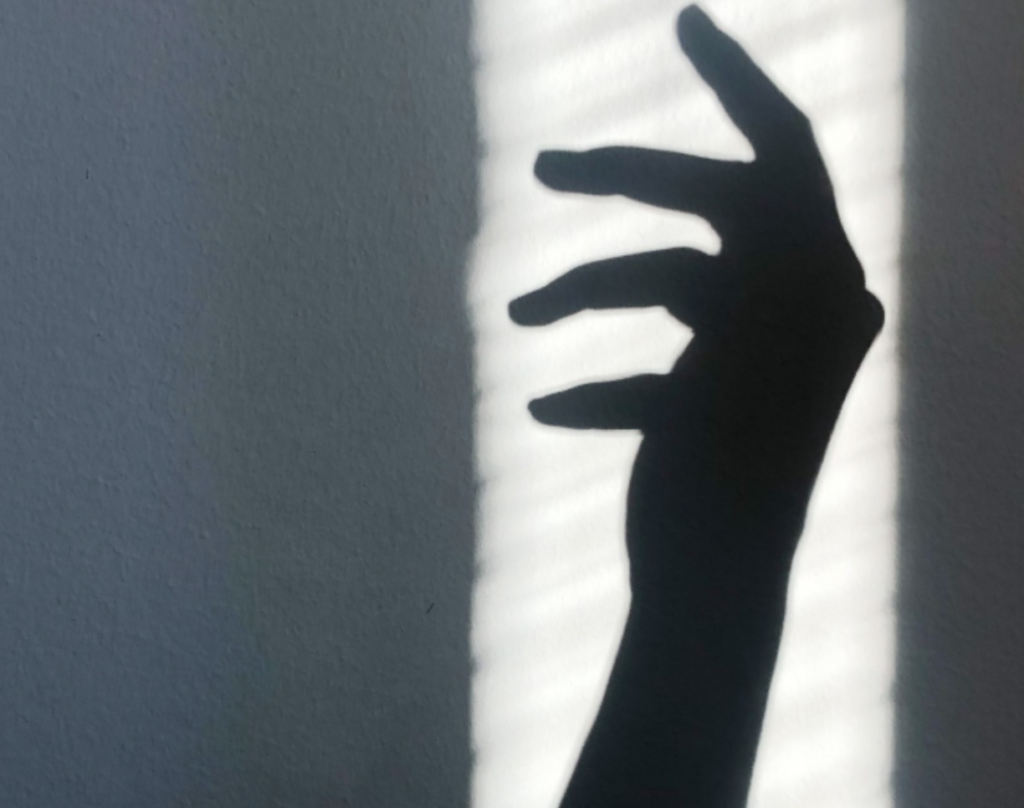

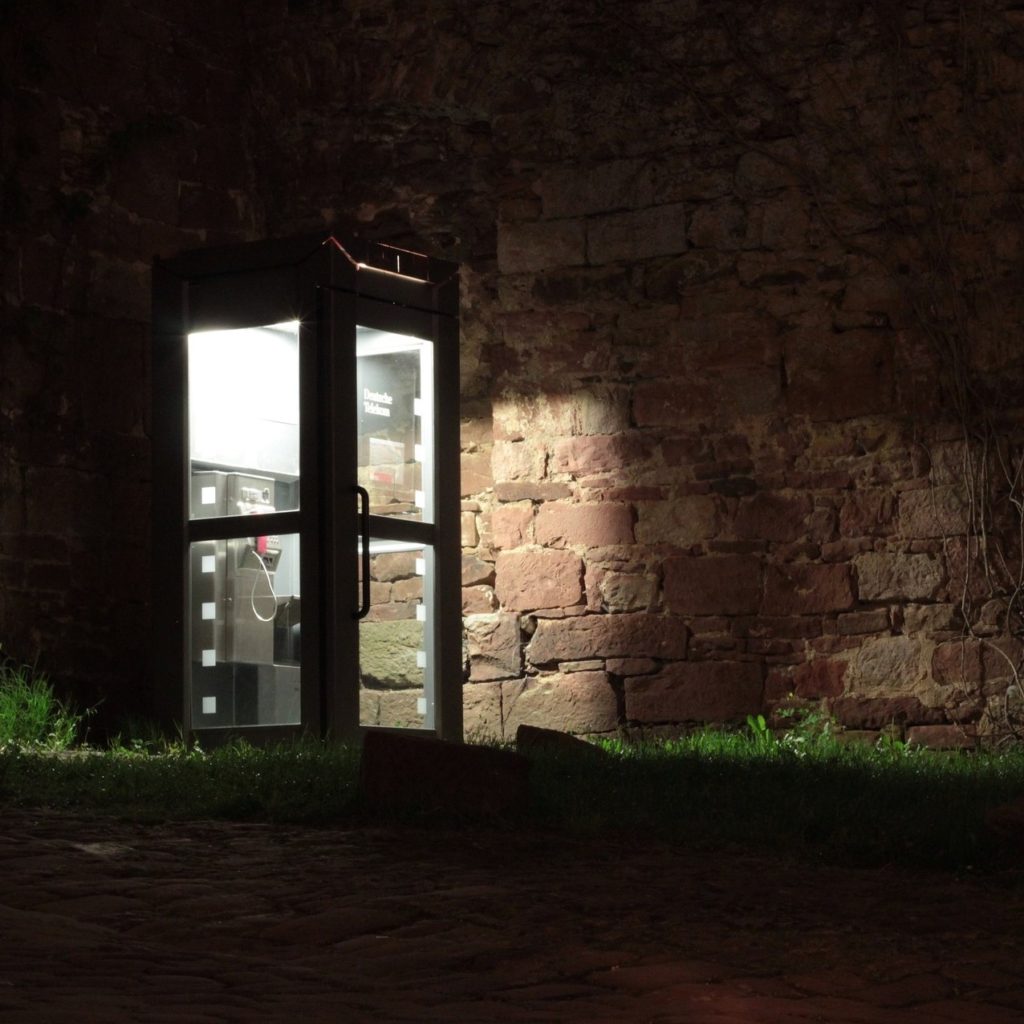

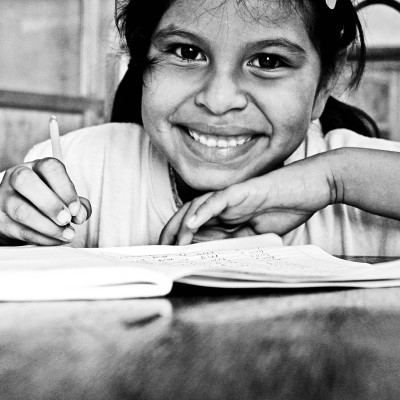

My husband hadn’t meant to render us in silhouette. He was a novice, the camera new and heavy in his hands. As we gazed out the window he didn’t realize that by aiming into the sun he’d cast us in shadow, erasing specifics. I could be any woman holding an infant up to the view. I could be you.

Proud of this accidental art, he had a large print made and framed. When he hung the photograph on our bedroom wall, I recognized its beauty, the quiet distillation of mother-love. But I also couldn’t forget the flash of anger that still hummed in the air as the shutter clicked. “Him, him, him. It’s always about him,” he’d yelled when I asked that he give us a turn at the window he’d been straddling, snapping shot after shot of a passing parade.

Him, that word, sputtered in triplicate, about our son, still new and heavy in my arms.

And yet, eventually, I grew to love that black and white portrait. I could even say it told me what to do.

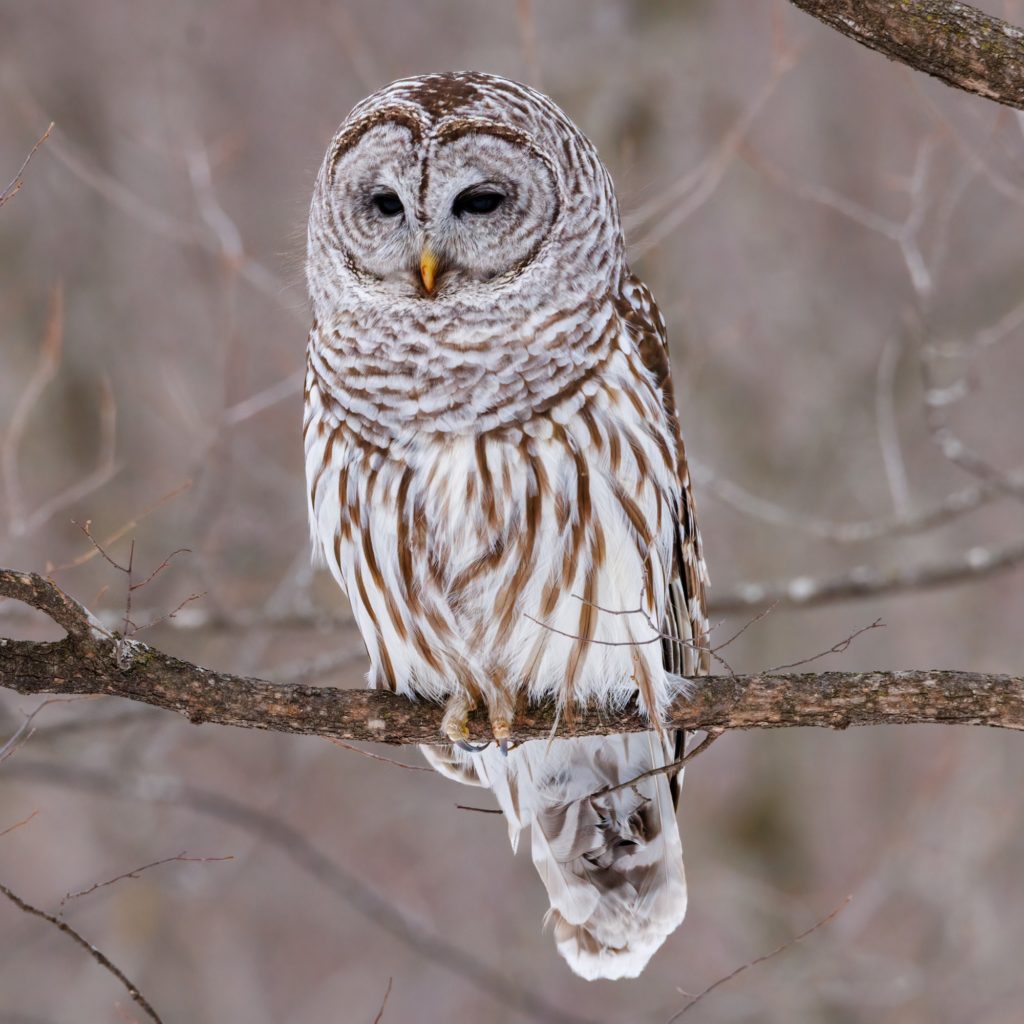

Here. Look at how our heads rest on each other. Notice the negative space, its one border made by my chin and my child’s ear, its other by my collar and the shoulder of his sleeper. That bit of light shaped by the way our dark forms touch—doesn’t it resemble an open-winged bird? Doesn’t it suggest flight?

Ona Gritz‘s nonfiction is listed among Notables in Best American Essays 2016, and has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, The Guardian, The Utne Reader, MORE, and elsewhere. Her books include the memoir, On the Whole: A Story of Mothering and Disability, and the poetry collection, “Geode.”

0 Comments