By Lynne Nugent

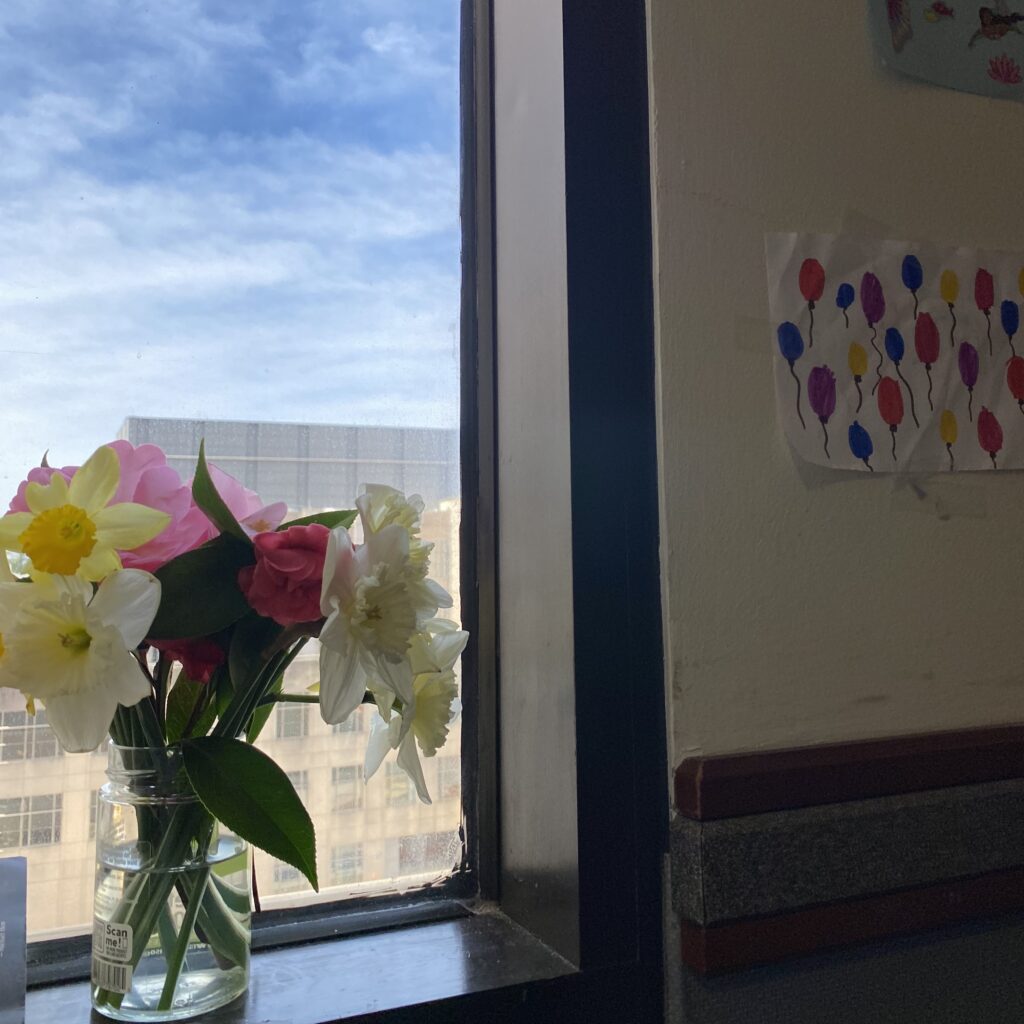

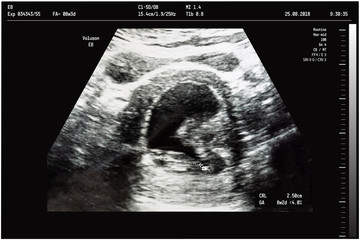

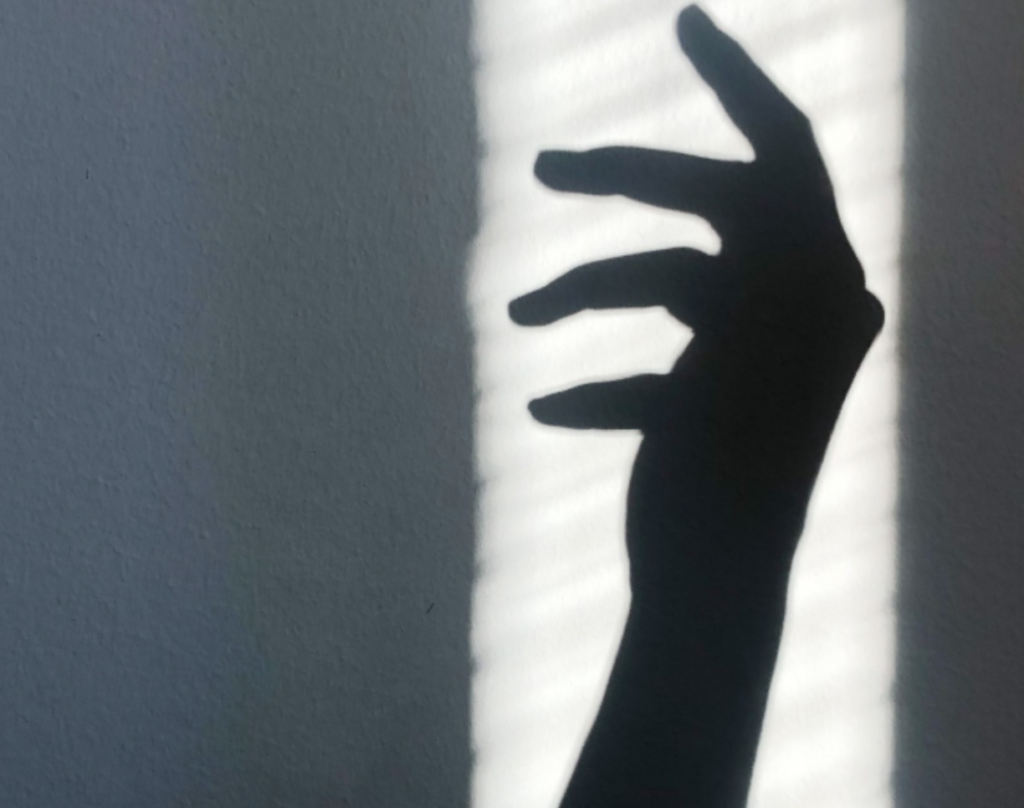

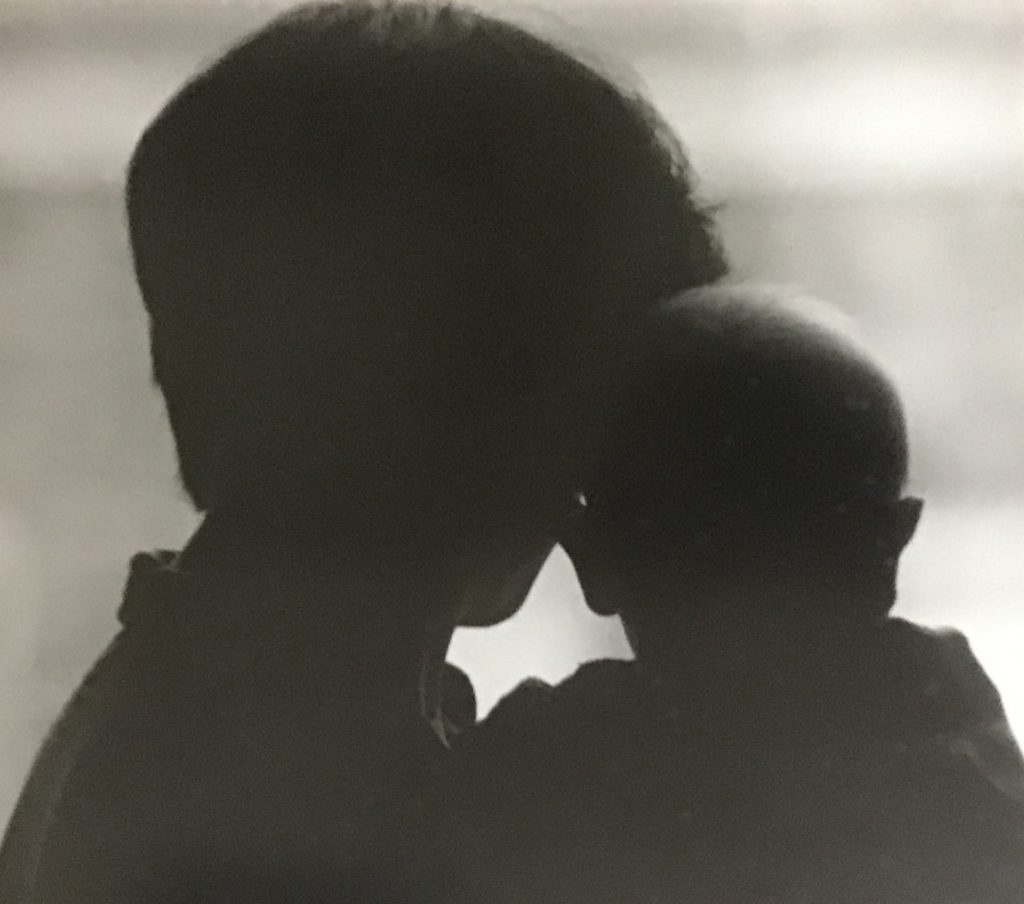

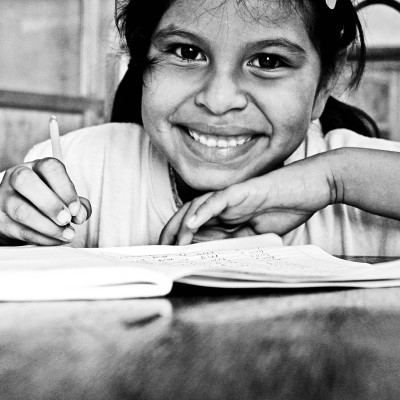

A few weeks into my second son’s infancy, I’ve noticed that when the lighting and angle are perfect, I can see his pulse on top of his head, at the place where the bones haven’t yet fused. Under the fine hair-fuzz, a nickel-sized patch of skin flutters in and out. It reminds me of that blinking shadow on my first ultrasound and how it thrilled yet undid me. Everyone talks about the sweetness of expecting a baby, but less about the terror at having created something so vulnerable. I spent each of my prenatal appointments barely breathing until the moment they swirled the Doppler through cold gel on my belly and relocated that rhythmic swishing.

Once he was born, I missed the certainty the pregnancy surveillance had provided. Newborns do so many things—go glassy-eyed, roll their eyes back, fall asleep on a dime—that in the rest of us would be considered signs of an aneurysm. A winter baby who’s swaddled up and sleeping shows few signs of life; when he buries his face in my arm and seems to subsist without breathing, I seek out the pulse for reassurance.

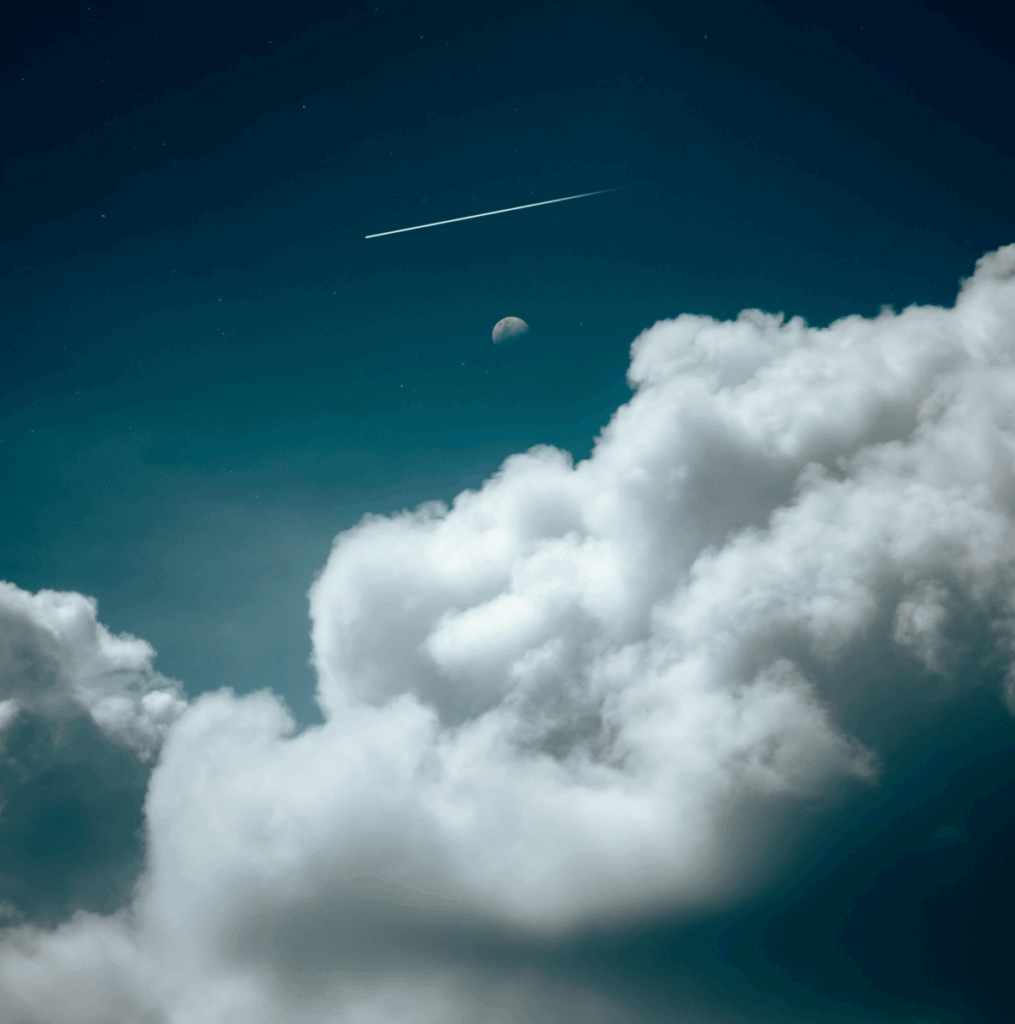

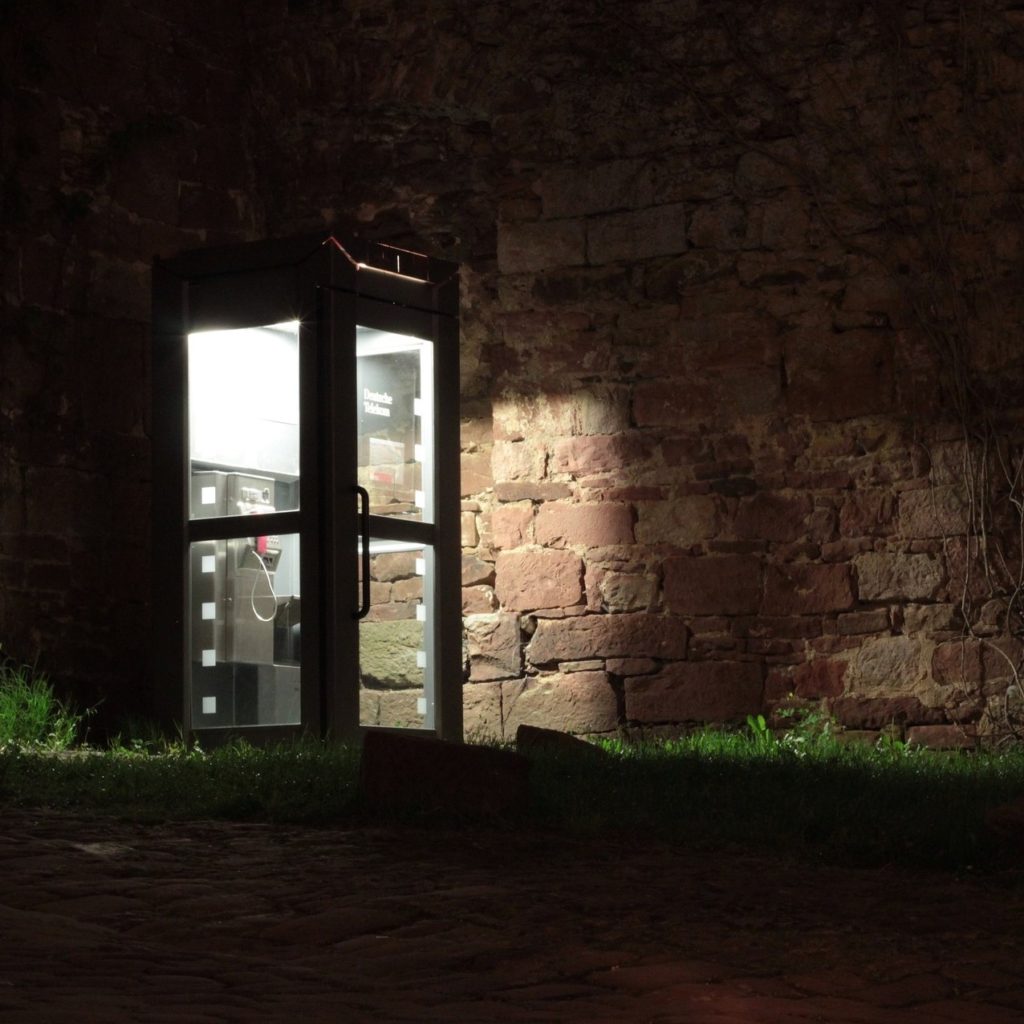

I know his skull will fuse and his hair will grow, and he’ll eventually become opaque to me in all the ways humans are opaque to each other. But for the moment, I’ve found what I need: semaphore, lighthouse, clock-tick in a quiet room, a telegraph tapping out in Morse code the message I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive.

Lynne Nugent works as managing editor of The Iowa Review. Her personal essays have appeared in the North American Review, Brevity, the New York Times, Full Grown People, Mutha Magazine, and Hippocampus Magazine. Find her at lynnenugent.wordpress.com.

0 Comments