By Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho

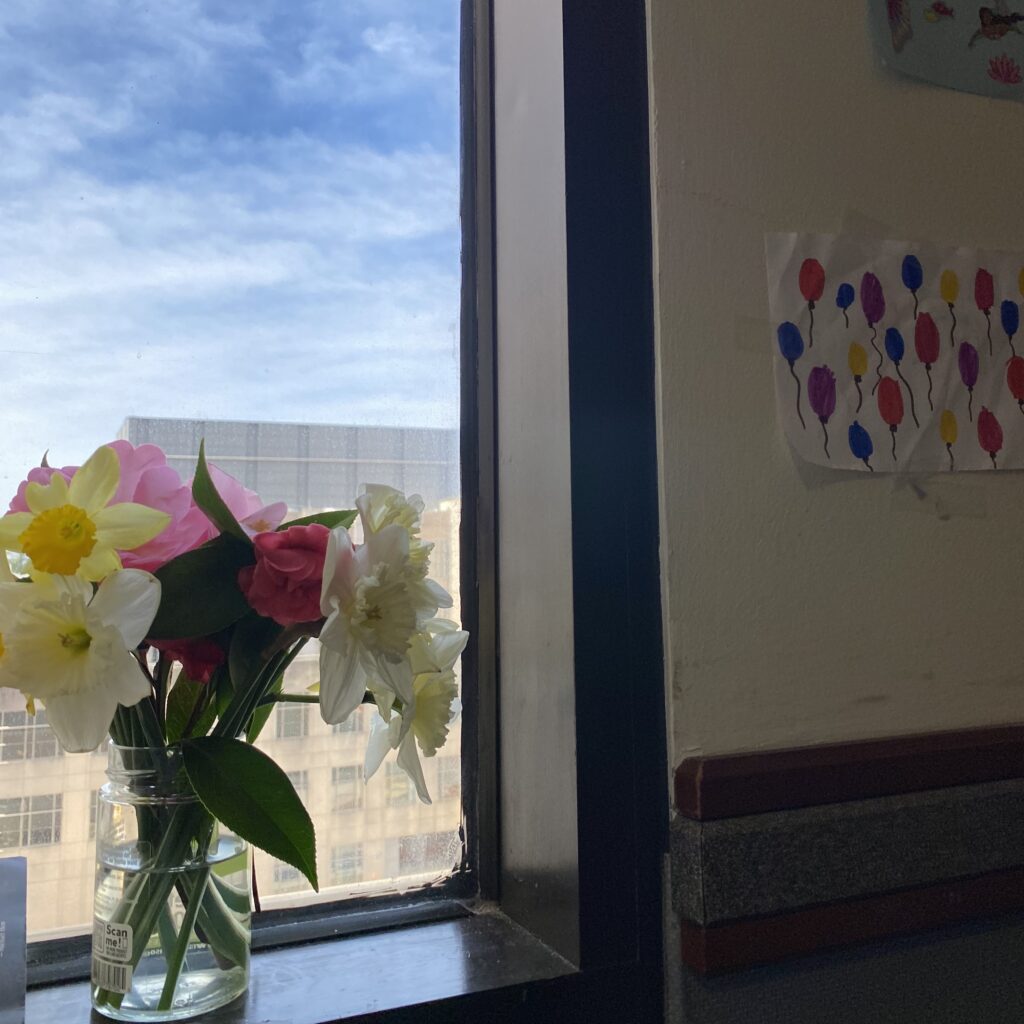

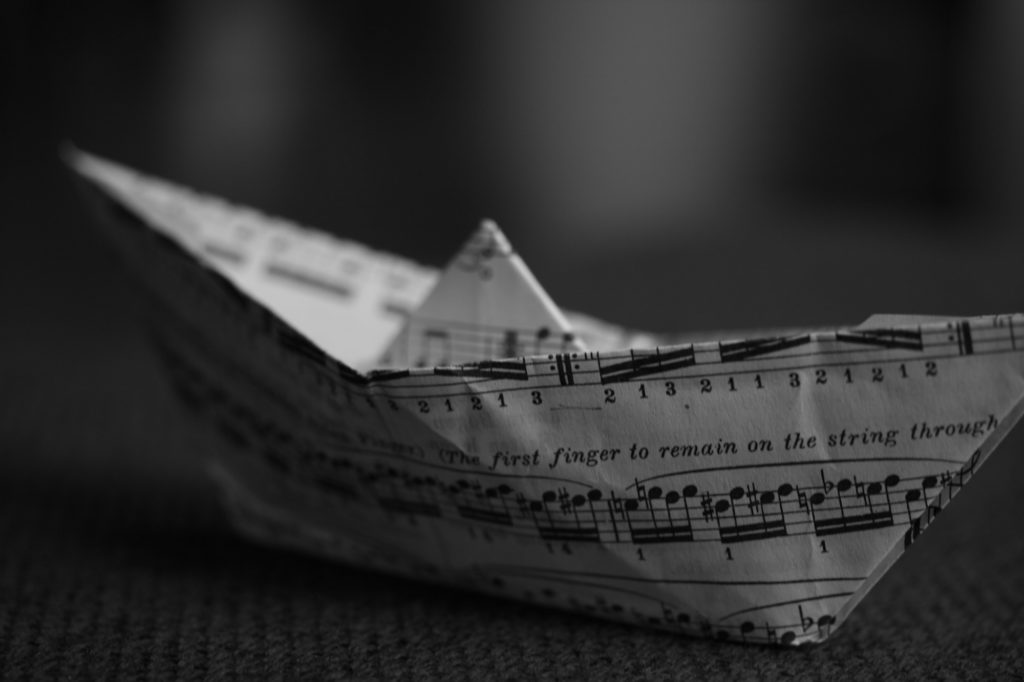

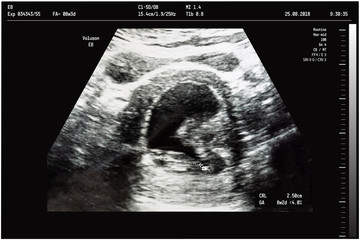

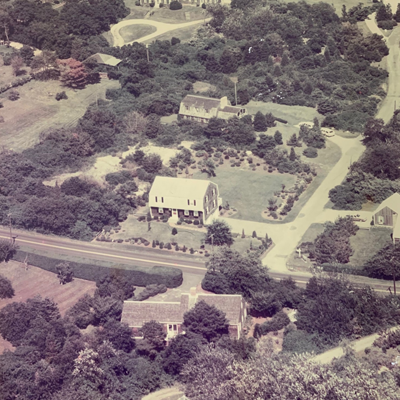

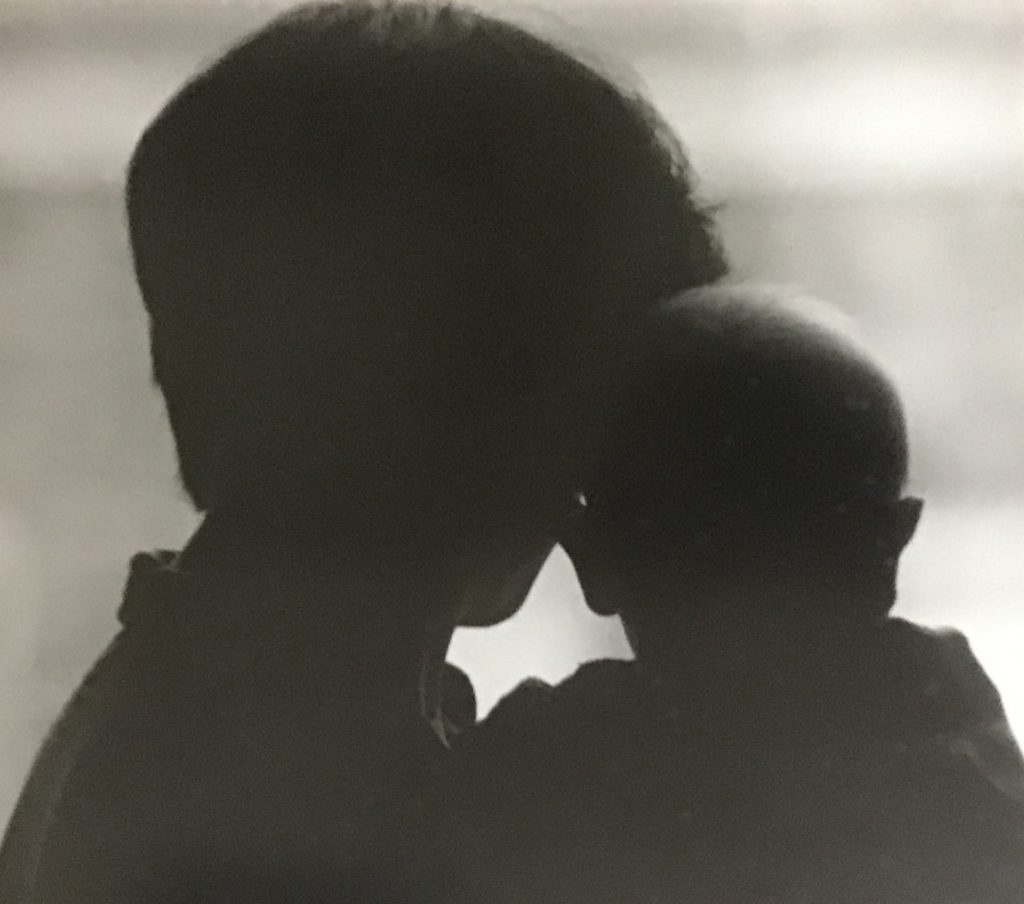

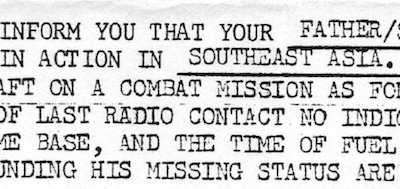

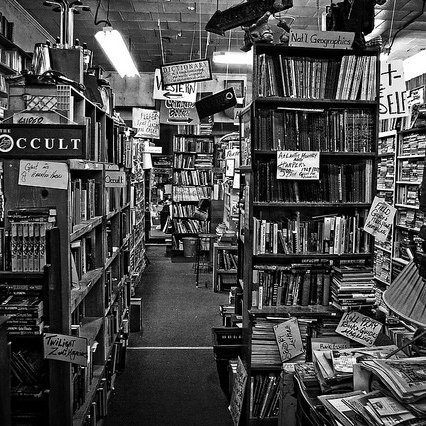

I recently framed the first piece of paper where my anglicized name appears. I paid extra for the non-reflective glass, so that viewers can see the details, including the black and white passport photo of my six-year-old self, looking very serious.

On the lefthand corner is a red seal with traditional Chinese characters, asserting the officialness of the document. The paper bears my birthdate, the names of my parents, my hometown in Taiwan, the fee paid.

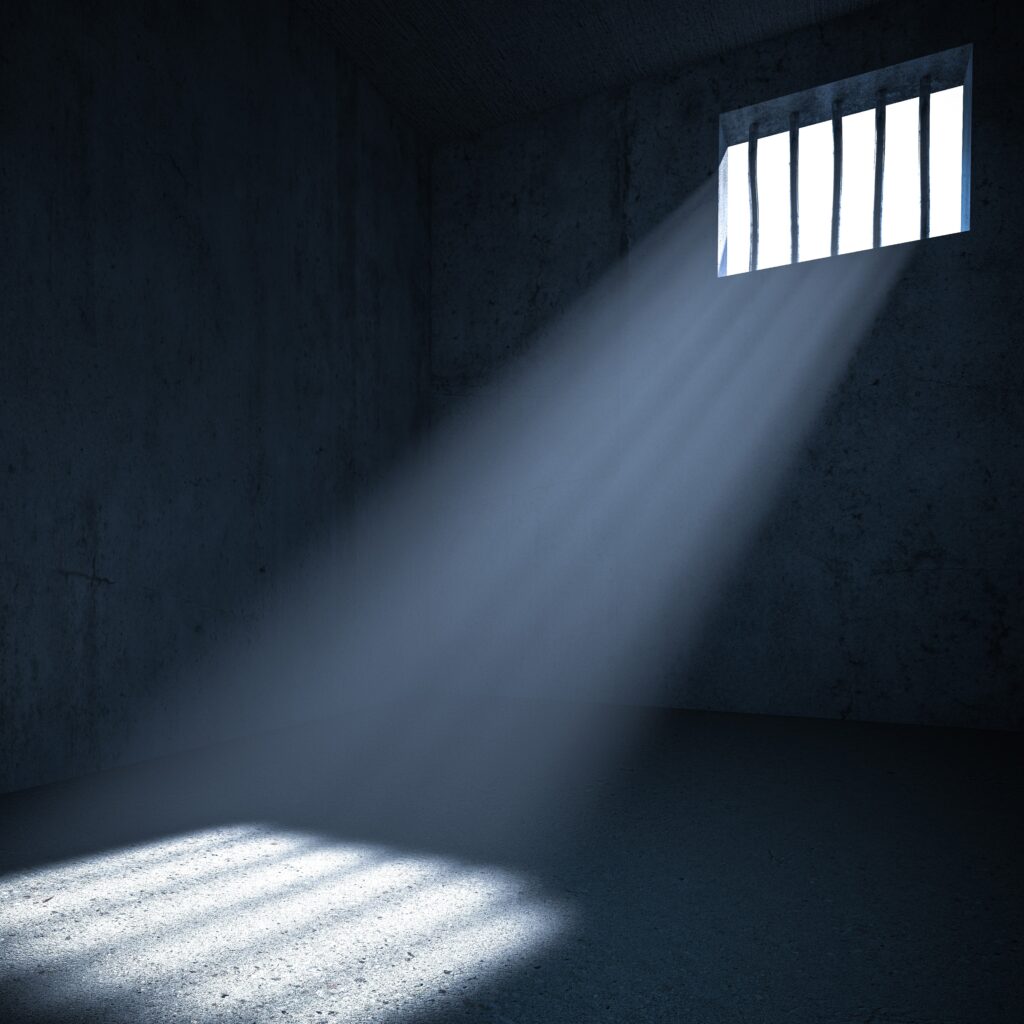

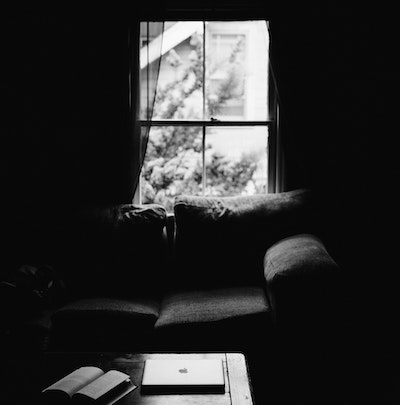

Deep creases line the paper north-south, east-west. Not even the best matting can straighten the years it’s spent in a dark drawer, folded in on itself.

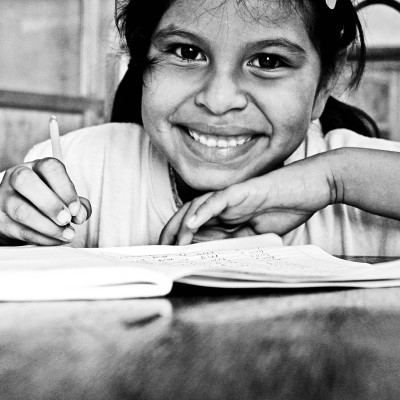

I hid it for all the time I was a newcomer growing up in this country, even after it no longer felt foreign, even after my country of origin grew foreign to me. When I became a citizen, I was still a child, and I pretended to have been born here. I lied to teachers and strangers, later, to friends and lovers. Maybe I lied because I was tired of being asked, confused why they kept asking when I sounded every bit like them. Back then, I didn’t know about internalized racism, even as I pretended, emulated everything except what my own skin refused to betray.

The paper, buried in a drawer for decades, is perfectly preserved. Despite the creases – or perhaps because of them – it has character. Like a late bloomer, unexpectedly bold, it is now on display for anyone to admire.

Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho identifies as Generation 1.5, inhabiting the liminal spaces between cultures and identities. Her short stories and personal essays have appeared in anthologies and literary journals. Wiley is at work on her first book, a memoir about growing up in a Taiwanese-Canadian “astronaut” family.

Image courtesy of the author

0 Comments