By Joanne Lozar Glenn

reposted from July 18, 2016

They saved it for Fridays. Every teacher had the same projects. Fall: iron leaves between waxed paper. Winter: chalk snow scenes on black construction paper. Spring: draw daffodils.

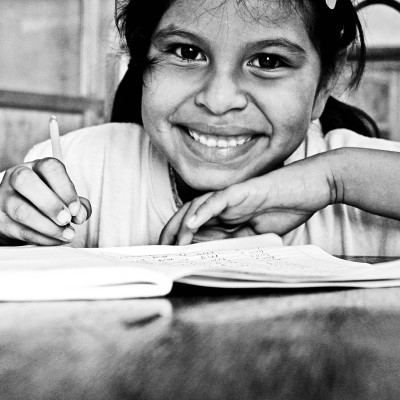

Except for Miss Malik. She was young, pretty, and not a nun.

“Bring lots of newspapers and a light bulb for Art this week,” she told us one day. So that night, after changing my uniform and before memorizing my Baltimore catechism, I made sure to tuck the supplies into my schoolbag. I liked Miss Malik. She’d put together a class poetry book and included my poem.

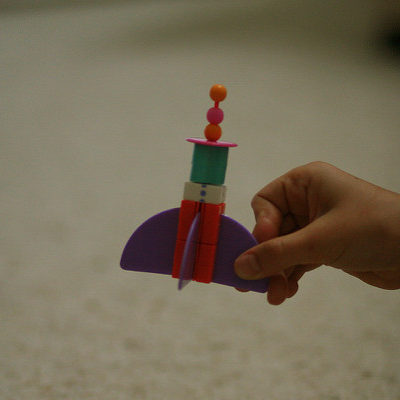

First Friday: We spread oilcloth on desktops to keep them clean, then layered each light bulb with strip after strip of hand-dipped newspaper soaked in wheat paste. Its slimy crust thickened our fingers till they could hardly move.

Second Friday: We painted the bulbs with tempera and set them on the windowsill to dry.

Third and final Friday: The big day. We were to smash the bulb against our desks until we heard the glass break.

“This is a maraca,” Miss Malik told us. “In Mexico, it’s used to make music.”

It was the ‘60s, and all we knew of Mexico was bandits wearing big sombreros in black-and-white TV Westerns. Miss Malik’s lesson let us glimpse another world.

And she’d taught us that something broken—even when it was broken on purpose, deeply, where no one could see—could still sing.

Joanne M. Lozar Glenn is an independent writer, editor, and educator based in Alexandria, VA. Her essays and poems have appeared in Amaranth Review, Peregrine, Under the Gum Tree, Ayris, The Northern Virginia Review, Hippocampus, and other print and online journals. An essay is forthcoming in Brevity.

0 Comments